Termites belong to the insect Infraorder Isoptera — from the greek words “iso” meaning “equal”, and “ptera” meaning wings. This refers to the equal size, shape, and venation of the four wings of winged termites or reproductives (alates). Termites are sometimes referred to as “white ants”, although they are both social insects and ants sometimes do occur in the same environments are termites, Australian ants do not attack wood and are not timber pests. It is therefore important to know the differences between ants are termites.

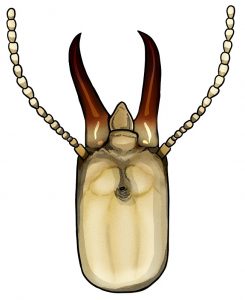

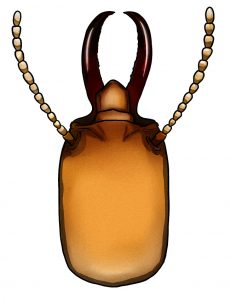

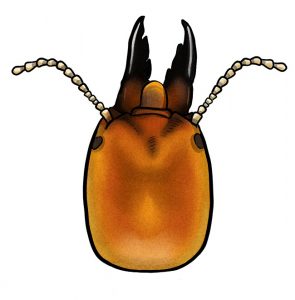

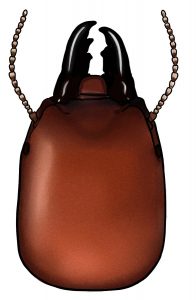

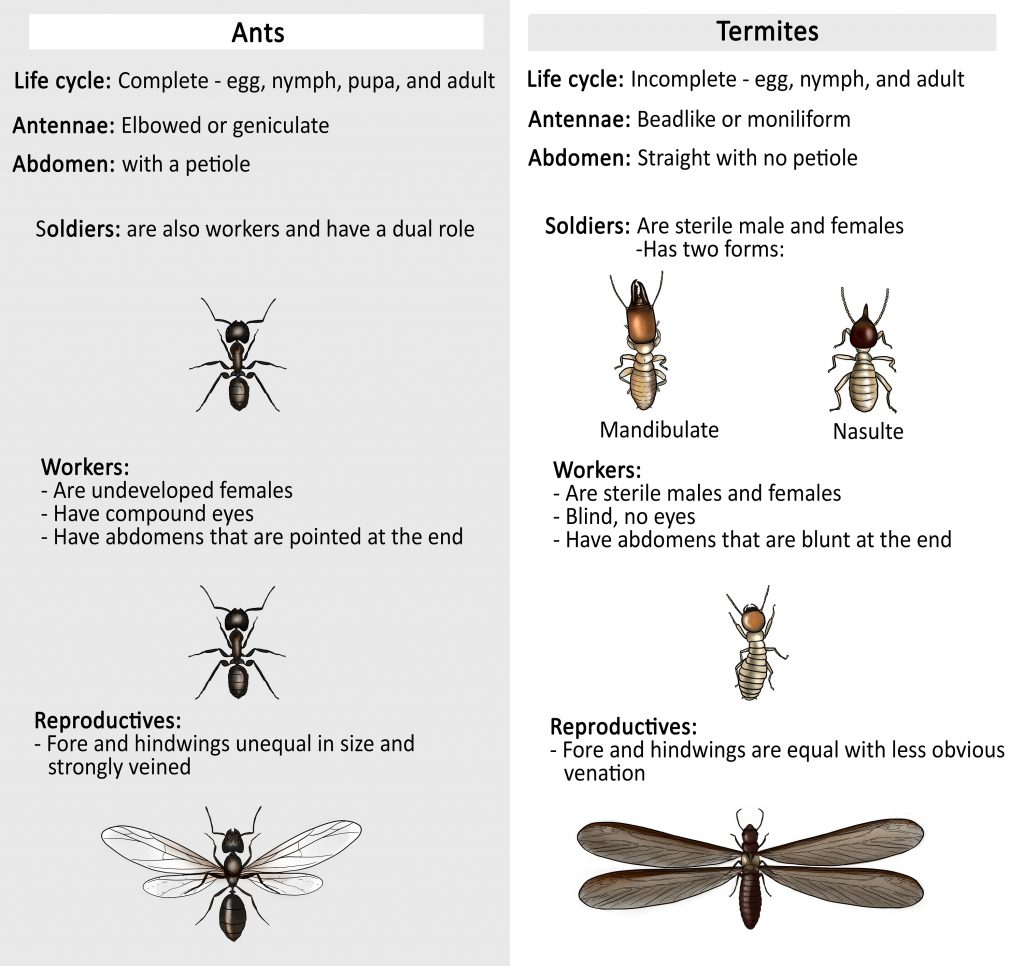

Termites are white to brown in colour, have straight beaded antennae, and have a straight abdomen. Their reproductives have equal-sized wings. Ants, on the other hand, vary in colour depending on the species, have elbowed antennae, and have a “pinched waist” or a petiole. Their reproductives have unequal wings; the forewings are bigger than the hindwings.

Biology and Behaviour

Termites are eusocial insects; they have the highest level of organization of sociality, in which a single female or queen produces the offspring and the non-breeding individuals cooperate with one another in feeding, protecting, and providing for the colony; each non-breeding individual has their own specific duties to fulfill. The size of a colony varies from about 100 individuals for some species of Kalotermitidae, to hundreds of thousands, and even millions for some species of mound-building termites from Termitidae, Rhinotermitidae, and Mastotermitidae. Colonies made by the workers have several forms depending on the species. Some species build mounds, some nest under the soil, and some nest above trees, or in dry wood. The form of colonies termites make may help in identifying the group or species, along with the morphological characteristics of the soldier caste.

Colonies

Termites live in nests or colonies that they’ve built themselves. The type of colony they build is genera and sometimes species-dependent. Nests come in different forms and the shape and placement can help in identifying the species, together with the region in which the infestation occurs, and the morphological characteristics of the soldier caste. Colonies can be in the form of ground mounds, subterranean nests, arboreal nests, pole nests, and tree nests.

Ground mounds

These come in several shapes and sizes like the tall and upright mounds of Amitermes spp. that can reach several meters in height in the Northern Territory, the smaller but robust mounds of Coptotermes lacteus, and the low-domed mounds of Nasutitermes exitiosus. They have unique external and internal structures depending on the species, for example Coptotermes lacteus build the external structures of their mounds with a thick layer of compacted clay, and the internal structures with digested wood, meanwhile Nasutitermes exitiosus build the external structures of their mounds with thin earthen materials, and the inner parts with soil, saliva, and faecal matter.

Ground mounds have a hard external layer to protect the fragile galleries and the royal chamber inside. Temperatures and humidity inside the mounds are maintained by the workers, which is critical to protect their soft cuticles from drying out. Many mound-building species eat grass but some feed on wood, which they access through their subterranean tunnels.

Subterranean

Many termite species build their nests below the ground. These nests provide termites with sufficient amounts of moisture and humidity. The sizes of subterranean nests can reach 6 m in height and 4 m in diameter.

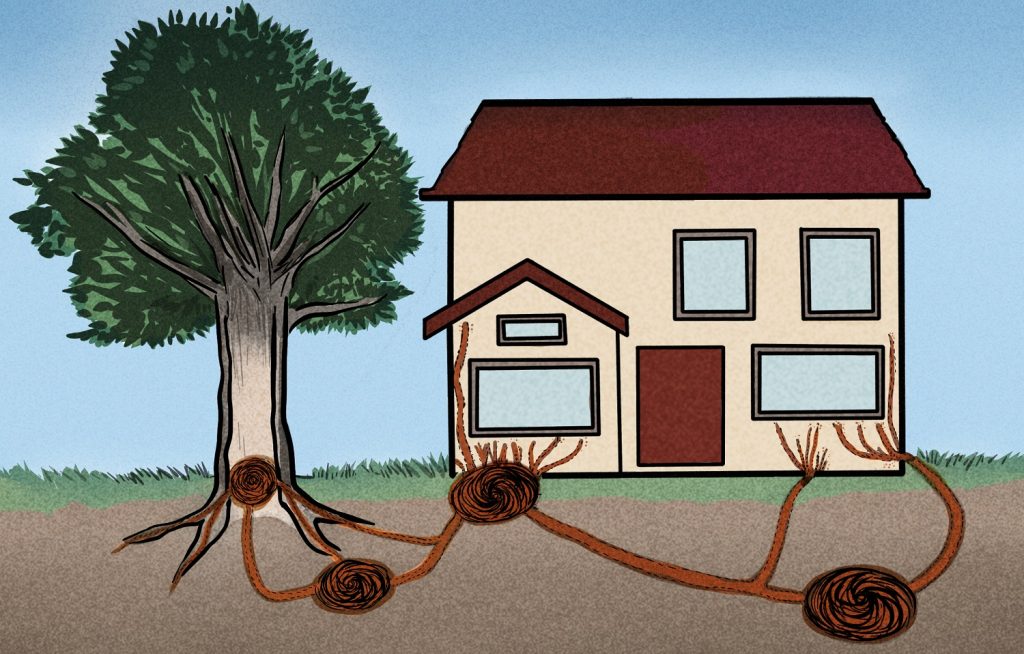

Subterranean termites like to nest inside tree stumps, roots, and waste timber, and when infesting live wood, they are often found nesting in the root crown area. Subterranean termites infest buildings and infrastructure when they get in contact with structural wood while building their tunnels underground.

Arboreal

This type of nest is built on trees and may be about 20m or more above ground. It is connected to another part of the colony located inside the root crown of the tree, and is connected by a shelter tube located on the exterior of the tree trunk. Termites use shelter tubes to attack decaying wood and to transport soil moisture to the nest. Nasutitermes walkeri and Nasutitermes graveolus are known to be the best arboreal nest builders. Microcerotermes turneri and M. serratus also build arboreal nests but they are monodomous or build a single nest unlike N. walkeri and N. graveolus

Pole

These are small nests that are found on transmission poles, fence posts, on the ground and on trees. These nests are often done by Microcerotermes turneri on the central coast of New South Wales and Southeast Queensland.

Tree wood

The species Neotermis insularis, Porotermes adamsoni, and many species in the Crypototermes genus are known to nest in wood. Cryptotermes spp. are drywood termites that feed on softwood, hardwood, drywood, furniture, and structural wood. N. insularis prefer softer growth rings, which is where the species got its common name “ring-ant”. P. adamsoni on the other hand feed on dead or decaying stumps. Both N. insularis and P. adamsoni are dampwood species.

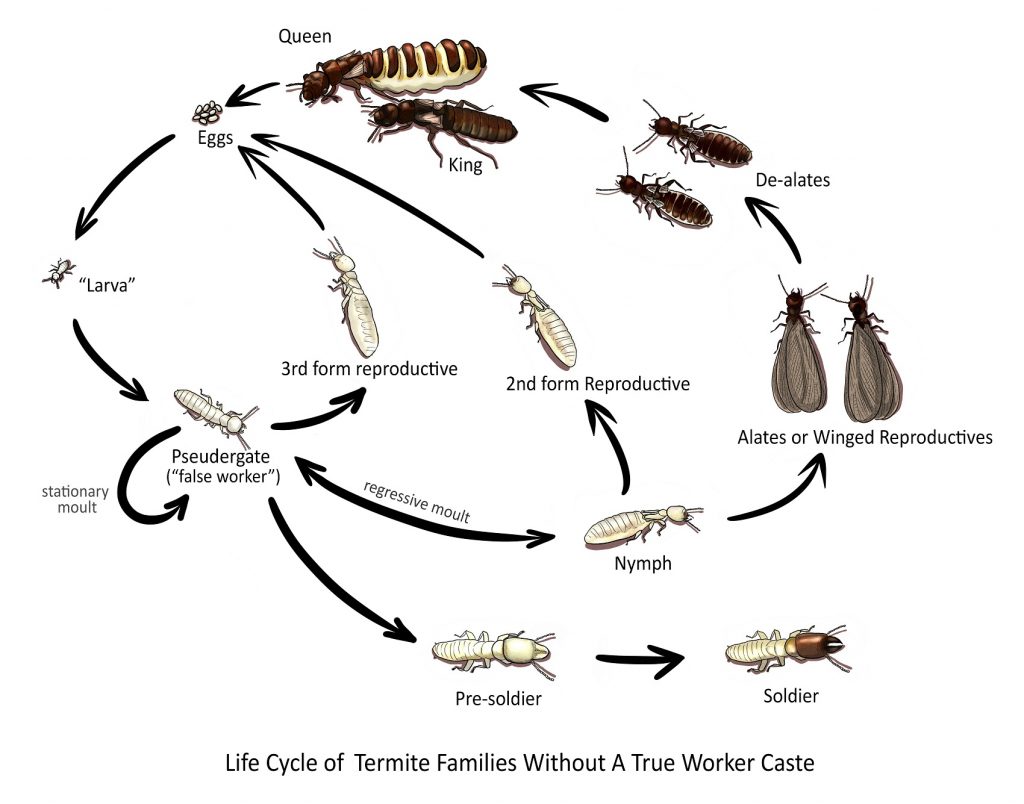

Life Cycle

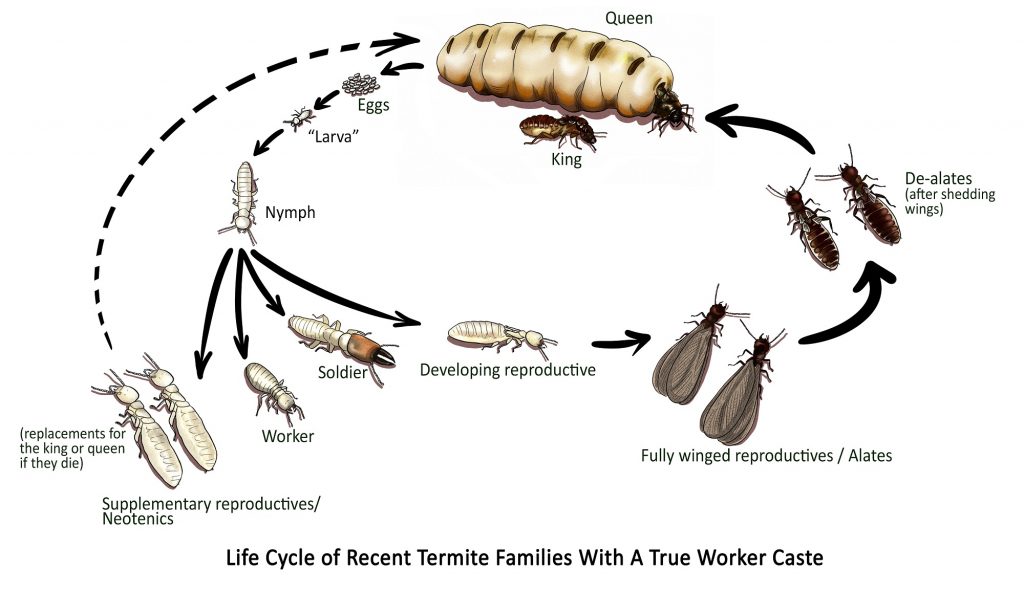

Termites undergo three life stages: egg, nymph and adult. Unlike ants, they do not have a pupal stage and therefore have an incomplete metamorphosis. Instead, the nymphs moult several times until they become adults, and then are assigned to different roles or castes by the king and queen of the colony.

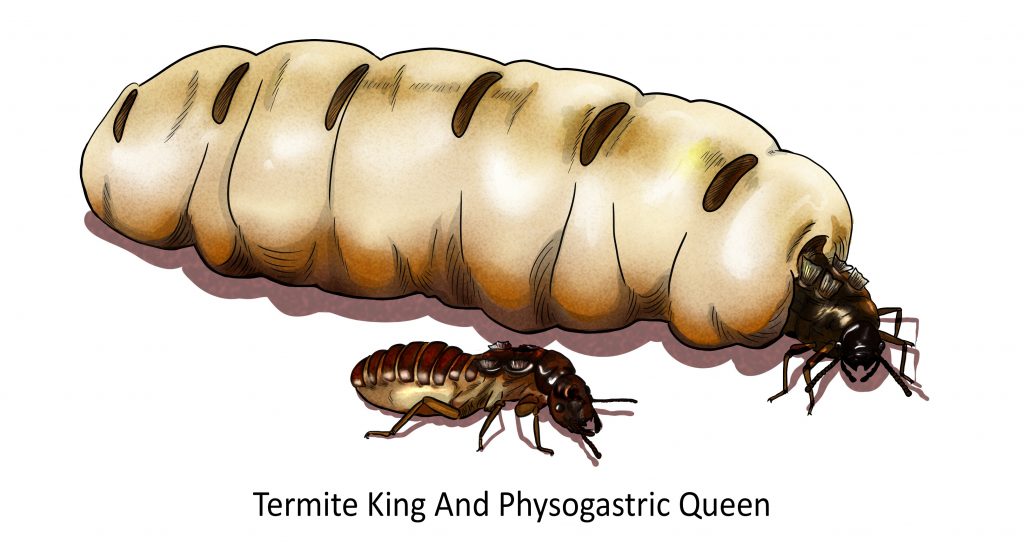

The King. The king’s job is to mate with the queen from time to time and release pheromones that would determine the castes of their offspring. The king may live over 20 years; if he dies, new kings will be selected from supplementary reproductives in the colony.

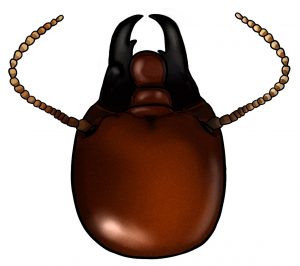

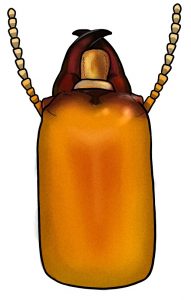

The Queen. The job of the queen is to lay eggs. Like the king, she also releases pheromones that determine the caste of her offspring depending on the needs of the colony. During the early developmental period of the colony, the king and queen tend to the young until there are enough workers to take on this task for them. Some termite queens have enlarged abdomens due to a characteristic called physogastry, common in species of Rhinotermitidae and Termitidae, and absent in Mastotermitidae. Physogastric queens often reach 30 mm or more in length.

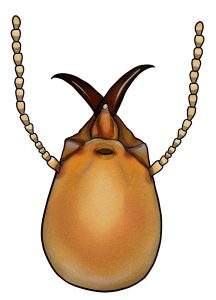

The queen can live more than 20 years depending on the species. Over time, the reproductive capacity of the queen declines and in event of her death, new queens will be selected from the colony called supplementary queens or neotenics. Supplementary queens are selected from reproductives developing in the colony; they will never leave the colony to undergo a colonizing or nuptial flight. These types of queens are called brachypterous queens. They are characterized by round wing buds that may vary in size depending on the developmental stage at which they were selected. They do not lay as many eggs as the primary queen, so it takes several of them to perform the reproductive task of the original queen.

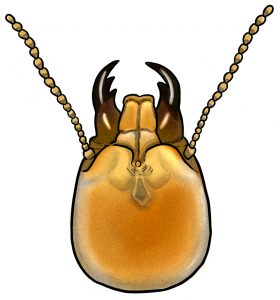

Macropterous queens are those that left the parent colony and have undergone colonizing flight — they were once fully winged. They appear darker than supplementary queens, have pigmented eyes, and angular stumps from their wings. They are also called true, or de-alated queens.

Egg. After the first mating in an attempt to make a new colony, the queen lays about 6-12 eggs in a few days or weeks, and fewer than 100 eggs during the first year. The number of eggs a queen lays will increase over time, eventually reaching more than a thousand eggs per day. In 5 years, the king and queen can grow a million colony members. A high-functioning queen can lay an egg every three seconds or roughly 30,000 eggs in a day.

Termite eggs are laid singly except for the species Mastotermes darwinensis. The eggs are shaped like a capsule and are white. Though they are small, they can be seen by the naked eye. The incubation period of eggs vary from species to species and environmental conditions but generally takes about a few weeks to a month.

Nymph. After hatching nymphs appear white and small. As they grow they undergo a number of moults or instars (depending on the species). These nymphs may develop into workers, soldiers, or reproductives (alates) depending on the colony’s needs.

Adult Castes

Termites have different forms or castes, with each caste having distinct physical attributes and performing specific tasks and duties for the maintenance and survival of the colony.

Workers. Termites can exhibit two different types of caste development pathways: the linear pathway and the bifurcated pathway. Members of termite families that evolved from ancestral lineages such as Kalotermitidae and Stolotermitidae, and some Rhinotermitidae genera have a linear pathway of caste development that lacks a true worker caste, instead, they have pseudergates or “false workers”. Termitidade, Mastotermitidae, and some Rhinotermitidae genera have a bifurcated pathway of caste development that has a true worker caste since they have two distinct lines of immatures: one that leads to the development of workers and soldiers, and that leads to alates.

True workers are sterile, blind, and very pale individuals that do the most amount of work among the other castes. They forage, store food, feed the king and queen and all the other castes, take care of the young, and maintain the tubes and nests of the colony. Pseudergates are totipotent immatures with very little morphological differentiation. Their development is flexible because they can moult into any form of adult (soldier, secondary reproductive, tertiary reproductive, or an alate).

There are two categories of pseudergates:

- Pseudergate sensu strico are individuals that develop from nymphal instars with wing buds to larval instars without wing buds through a phenomenon called regressive moulting. They show ancestral development flexibility because they are common in small wood-dwelling termite families but can also be present in large colonies of Rhinotermitidae and Termitidae.

- Pseudergate sensu lato or “false workers” are larval and nymphal instars that perform the work in the colony. They are also capable of moulting into soldiers by a stage called pre-soldier, into alates, or into secondary and tertiary reproductives.

The genus of drywood termites, Cryptotermes, is a good example of termites without a true worker caste.

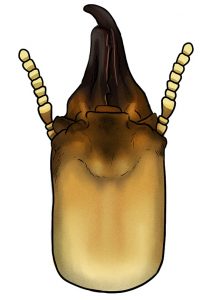

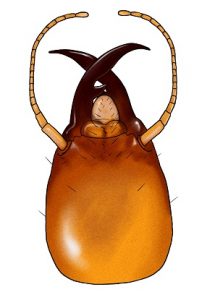

Soldiers. They are the easiest to caste from which to identify the species. Termite soldiers have distinctively shaped and darker heads, and are typically bigger than workers. Newer colonies have fewer numbers of soldiers than bigger colonies since more workers are needed to build the colony in the early stages. Soldiers function as the protectors of the colony against invaders, particularly ants. Some species, particularly in Shedorhinotermes spp., have major and minor soldiers. Major soldiers are stationed closer to the central nest and major soldiers are further away from the nest.

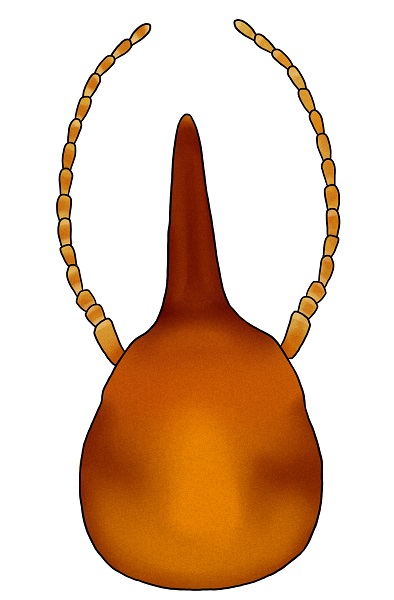

There are two types of termite soldiers, mandibulate soldiers and nasute soldiers. Mandibulate soldiers have prominent mandibles, and nasute soldiers appear to have a pointed snout with small mandibles beneath them. All the soldiers of the genus Nasutitermes spp. are nasute. Soldiers live for one to two years.

Reproductives. They are the sexual forms of a colony and may be kings and queens in the future. They develop inside the colony and after their last moulting stage, they emerge as fully winged reproductives or alates. They have compound eyes and are darker in colour than any castes, and are larger in size. They also have thicker cuticles which enable them to resist water loss when they leave the parent colony to make their own.

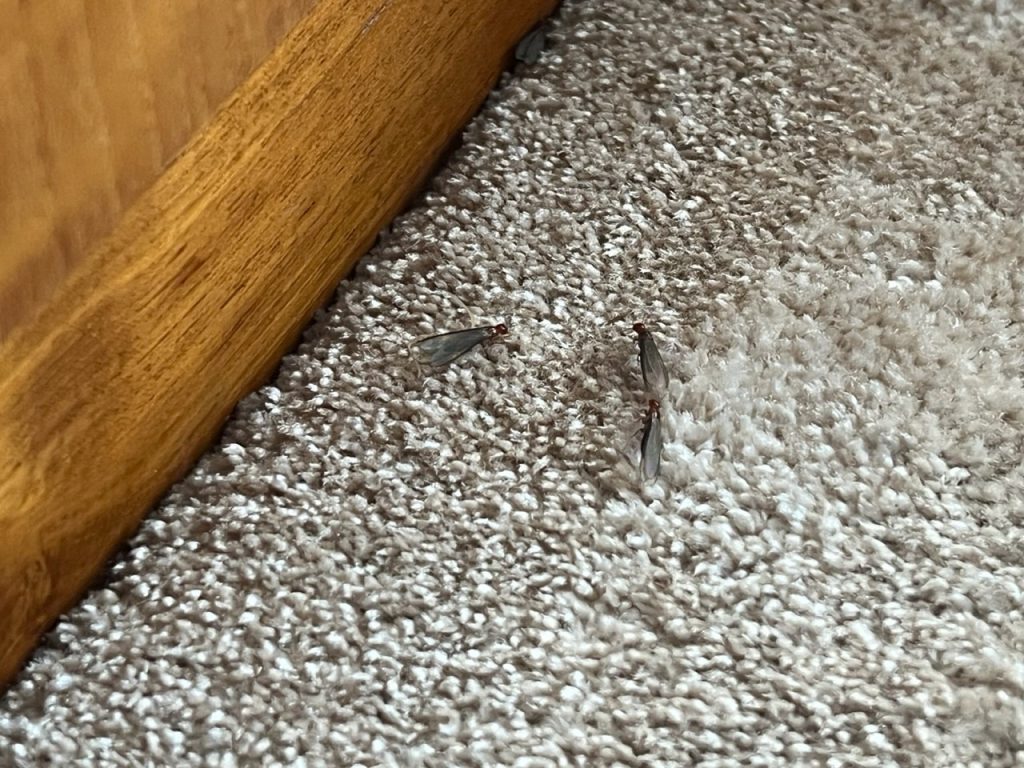

They undergo a mating process called colonizing flight or nuptial flight, usually in the early summer months of November-December and March-April periods when the temperature and humidity outside are similar to that inside the colony. This phenomenon can be observed when there is a swarm of alates under street lights during night time. Only 1% of the thousands of alates survive looking for a mate. The ones that survive lose their wings and males follow females in search of a suitable site to start their new colony.

Food and Feeding Behaviour

Termites feed on cellulose in many wood species whether it be softwood, hardwood, or wood products. They also feed on leaves and grass. Despite this, the feeding behaviour of termites also depends on the species; there are some species that prefer damp or decaying wood, and there are some species that prefer to feed on grasses. They get their protein and carbohydrates from fungi that decay wood.

Termite Damage

Termite damage on wood often looks like water damage. Termites eat through wood that cause wooden structures to bend, buckle, and sag. Signs of termite feeding can also be determined by the presence of mud tubes, termite frass or termite excrement, discarded wings, and mildew or mouldy smell.

Termite infestations cause million-dollar losses to houses each year. On top of that, they also cause damages to factories, bridges, commercial properties, forests, and orchards that add up to hundreds of millions of dollars more in control and repair costs.

Termites can also feed on the plastic covering of wires which can lead to power loss, and in some cases fire. They attack the root crowns of young trees that cause them to dry up and die. They can also hollow out the trunks of mature trees, making them structurally weak against heavy rain and strong winds.

Three Main Categories of Termites

Pest controllers often classify termites into three categories which are:

- Subterranean

- Drywood

- Dampwood

This classification is based on the behavioural characteristics of termites, their sites of occurrence and their habitat. This may be an oversimplification of how termites are identified, but it is a good and simple basis for classification, especially when having to come up with control measures without having to consult taxonomists.

Subterranean. Subterranean termites invade buildings from their tunnels below the ground. This group includes mound-building termites, arboreal termite species, and termites that live both inside trees and in the ground. High humidity and favourable temperature are critical for termite survival, so these termites manipulate the soil moisture to keep it within a range of 25-35℃ and they maintain the humidity close to 100% to keep their cuticles from drying out. To achieve this, they need to keep their nests sealed and that is why the presence of these subterranean termites is often undetected. However, the activity of some species of subterranean termites can be detected by mud tubes that they make on the surfaces of wood, often on walls, ceilings, and floors of buildings. Species from the genera Amitermes, Coptotermes, Microcerotermes, Nasutitermes, Schedorhinotermes, and Heterotermes are classified as subterranean termites.

Coptotermes acinaciformis and Schedorhinotermes intermedius are species that make their nests inside trees or underground. While C. acinaciformis can also build above-ground mounds, S. intermedius almost exclusively builds “underground mounds”; they are two of the most damaging species of subterranean termites in Australia.

Drywood. Drywood termites do not need any source of water in order to survive other than the humidity that they get from the moisture content of the timber they infest. They are found in tropical areas where humidity seldom fluctuates and remains almost at a constant 75%. Timber usually has a moisture content of 12-18%, but drywood termites can survive in even dried inland areas. Drywood termites do not form central colonies and exist in many small independent colonies. A sign of drywood termite infestation is piles of termite frass or dry fecal pellets found near the infested timber. They look and feel like coarse grains of sand when touched.

Species from the genus Cryptotermes are true drywood termites. Cryptotermes brevis, commonly called West Indian Drywood termite or powderpost termite, is an introduced species known to infest buildings and infrastructures in Queensland. It is considered to be the most invasive and widespread species of Cryptotermes because of its small size and the fact that it can be transported in very small species of wood — which is most likely how they made their way to Australia. Cryptotermes primus is a species native to Australia that is also considered a true drywood termite.

Dampwood. Dampwood termites feed on old, decaying tree stumps, and dead trees. They depend on the decaying trees or timber they attack for moisture, and they form their tunnels in the softer growth rings. They are not considered major pests of buildings, although they can attack damp and decaying wood structures in moist and poorly ventilated areas. Dampwood termites found in trees don’t typically form subterranean galleries, and often do not have contact with soil. Like drywood termites, they do not form parent colonies and live independently in many small groups. Species from the genera Porotermes, Stolotermes, Kalotermes, and Bifiditermes are dampwood termites.

Termite Classification

There are more than 300 species of termites in Australia, but only a few cause significant economic damage to houses, timber, and other products that contain cellulose. It is very important for technicians to know how to identify termite species in order to give sound advice to the client. In order to do so, one must have at least a x10 hand lens or a pocket microscope. The size and morphological characteristics of the soldier caste, distribution, feeding habits and damage are all necessary information in identifying a species. However, sometimes it’s best to collect samples and send them to a termite specialist for accurate identification.

Collection. In collecting termite specimens, if possible collect several of each caste and carefully place them in tightly sealed plastic or glass vials with 70% ethyl alcohol. On a piece of paper or card, write down the date, location of collection, collector’s name, and other useful information like the appearance of the nest, did the infestation occur in a log, what kind of tree, in a house, etc., and be sure to use a pencil in writing so it won’t smudge if ever the paper gets wet.

There are five termite families present in Australia. Three of the five families are primitive, meaning they do not have a true worker caste, and the labour done by workers is carried out by immature termites (pseudo-workers or pseudergates) which, when they moult do not have any significant change in their size. The other two families have recent worker cates. The diagram below shows the termite families and the termite species often encountered in the field.

Important Termite Species

Other Termite Species

Termite Control and Management

Inspection or Survey

The first step in controlling termites is to perform a thorough inspection or survey of the premise. This is a crucial step that will determine whether or not there is a termite infestation present on a property. Before conducting an inspection, technicians must have the right tools like a flashlight for inspecting dark spaces, and a long sharp object that can be used to probe termite damage and expose termite galleries in wood. Check spaces that are likely to have termite damage like basements and crawl spaces. They should also pay attention to wooden structures like support beams, subfloors, wooden decks, fence posts, and areas where concrete meets wood.

Before initiating any treatments, it is also very important to be able to identify the termite causing the infestation because this can tell a lot about how the infestation should be treated and what is the best way to go about it. Out of the few hundred termite species found in Australia, only about six are considered economically important pests and they are all the subterranean type.

Common Signs of Termite Activity

Termite inspections rely on visual evidence and signs that a building or structure is internally and/or externally damaged. Termite activity can be detected by the presence of the following:

Shelter tubes. Termites make tubes from soil and wood combined with their saliva to protect them from predators and to prevent desiccation during their comings and goings from the main colony area. They also use shelter tubes to maintain contact with food sources that are not accessible any other way. Shelter tubes usually originate from the ground and are found on walls and foundations. Sometimes, a free-hanging “stalactite” tube can be found.

Subterranean tunnels. Subterranean termites attack timber in contact with soil through their underground tunnels. Coptotermes acinaciformis make underground tunnels that are 200 mm below the ground with a radius of 50 m or more from the nest. Nasutitermes walkeri usually build tunnels on the surface of the ground or a few centimetres within the soil.

Flight holes in trees. Subterranean termites often make their nests inside tree trunks and the root crown area. When the alates are ready to take the colonizing flight, the workers cut longitudinal flight holes in the trunk. Once the alates have left, the workers seal up the holes. The tree then develops raised callous tissues, also known as blowholes, which can be the only external evidence of a subterranean termite infestation.

Flight tubes. Workers build small flight tubes projecting horizontally from infested timber or walls when the colony is ready to release alates. Once the alates leave the colony, the workers seal the tubes.

Excavation of wood. Different termite species have their own style of excavating wood:

Coptotermes acinaciformis make narrow grooves inside the wood.

Nasutitermes exitiosus hollows out the wood.

Mastotermes darwinensis makes large galleries running longitudinally with the grain of the wood. Additionally, Mastotermes is also known for ringbarking tree trunks.

Schedorhinotermes intermedius excavates wood around nails in flooring.

Earthen packing. Termites that work inside wood may produce mud-like packing on the outside surface. They can also be found in wall cavities, and over wall foundations where they meet the flooring and joints.

Termite noises. Mastotermes darwinensis can be heard feeding on wood. Other termites can also be heard using a stethoscope or other sound-amplifying devices. An audible tapping sound can sometimes be heard from Coptotermes acinaciformis in response to tapping by a technician during an inspection. This is caused by soldiers tapping their heads and mandibles on the wood as a warning signal to the members of the colony.

Collapsed timber. Termite infestations often go unnoticed until something collapses; the first sign of termite activity is the sagging of support beams, or accidentally finding hollowed-out wood structures.

Odour. Some termites have a distinct odour associated with them, Nasutitermes exitiosus nests when opened, have a distinct smell that is thought to come from the defensive fluid they release from their fontanelle.

Presence of alates. The presence of alates, dead or alive, and their discarded wings in an area is a sign that there is probably an infestation nearby.

Tree nests. Arboreal nests are easily spotted even in early developmental stages. Some termite species make their nest in the centre of tree trunks or in the root crown area. Their presence can be confirmed by callous tissues or exposed workings where a branch has been broken off. Coptotermes frenchi, Schedorhinotermes intermedius, and sometimes Coptotermes acinaciformis build nests in the subsidence area right under the root crown. When a metal rod is probed in the centre of the tree, there will be a sudden lessening of resistance as it enters the softer material. If the rod is left for a period of time and then pulled out, the rod would be warmer than the outside temperature.

Collapsed Timber

Early detection is key in stopping termite infestations before they cause structural problems. Since their activity is often hidden, the first signs for termite inspectors are typically the aftereffects of their feeding. Watch for sagging floors and ceilings, which indicate termites have eaten away at support beams. Hollowed-out structures like skirting boards, window sills, and door frames can also be giveaways. Unexplained loose door hinges due to weakened wood around the screws are another potential red flag. By recognising these signs, termite inspectors can identify and address termite problems before they become extensive.

Neighbour Experience

If you cannot find the source of the termite activity in the building, check with the neighbours. They might know if there have been termite problems in the area before. This can help pinpoint where the termite nest might be located.

Inspection aids

While termite inspection tools can definitely help find these pests, it’s important for technicians to understand what each tool does well and what it misses. Manufacturers offset training on their equipment and take advantage of this key.

Remember, homeowners and buyers rely on our inspection to make big decisions. So combining the information from these tools with signs of activity and damage is the best way to ensure a thorough and accurate inspection.

The non-pest species

Many recently identified termite species in Australia do not target houses. These termites feed on grass, compost heaps, and rotting wood found on the ground. This means it is crucial to identify the specific termite before recommending expensive treatments to customers because they might not be destructive at all.

Locating and Controlling active termites

Minor termite species can often be found in dead wood, mulch, and even plant stakes, however, discovering these termites does not automatically necessitate treatment, and these particular species may not pose a threat to buildings. To determine the best course of action, accurately identify the termite and assess its potential for causing damage. With this information, treatment options can be discussed with the homeowner.

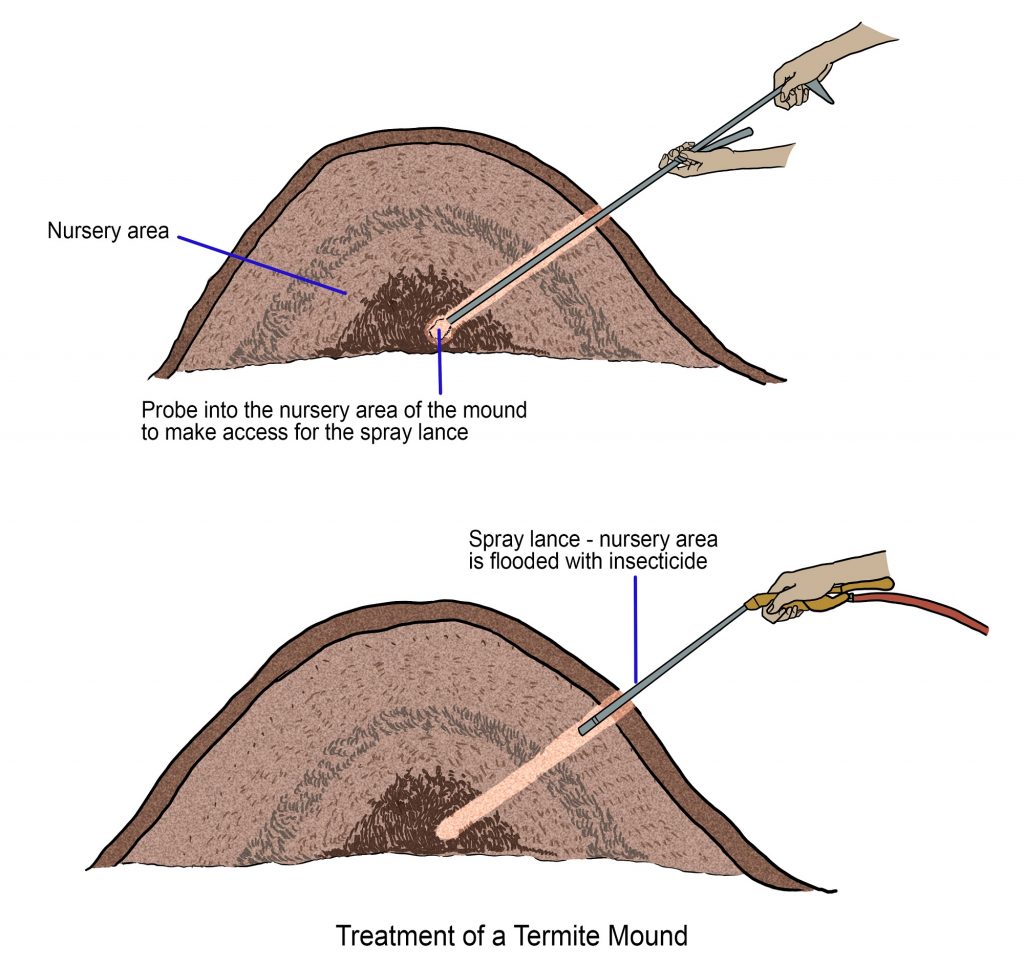

Mound colonies

In suburban and semi-rural areas, it is common practice to destroy mounds, even if it’s just to get rid of the eyesore. Mounds near buildings will likely need removal anyway, so doing it upfront makes sense. The key is to physically destroy the central part of the nest underground, where the royal chamber and nursery are located. Break this area up thoroughly to expose the nest to the elements and predators (other insects and animals) will usually destroy the colony. However, there’s a chance surviving queens could rebuild the mound.

When dealing with multiple termite mounds that need to be destroyed, and their visibility is not an issue, using insecticides can be a more efficient and less labour-intensive method. While the type of insecticide is not crucial, proper application technique is key. Holes should be drilled through the mound’s tough outer wall and into the lower central structure of the nest. For dust application it is advisable to make several holes and ensure it puffs out of other holes, indicating it is reaching the entire nest.

Liquid insecticides are more reliable than dusts and should be used in sufficient quantity to thoroughly wet or flood the entire nest interior. Using too little can cause the insecticide to bypass the nursery area. It’s more effective to use a larger volume of a lower concentration than a smaller amount of a higher concentration, always following label directions.

Fumigants hold promise for the treatment of nests located within mounds or trees. The success of this type of treatment lies in the inherent nature of the nest itself, as it functions as a climate-controlled environment. The introduction of fumigant gas has a limited escape window once the entry points are resealed. In theory, any insecticidal fumigant should prove effective due to the trapped gas. Always follow the safety precautions on the product label.

Colonies in trees

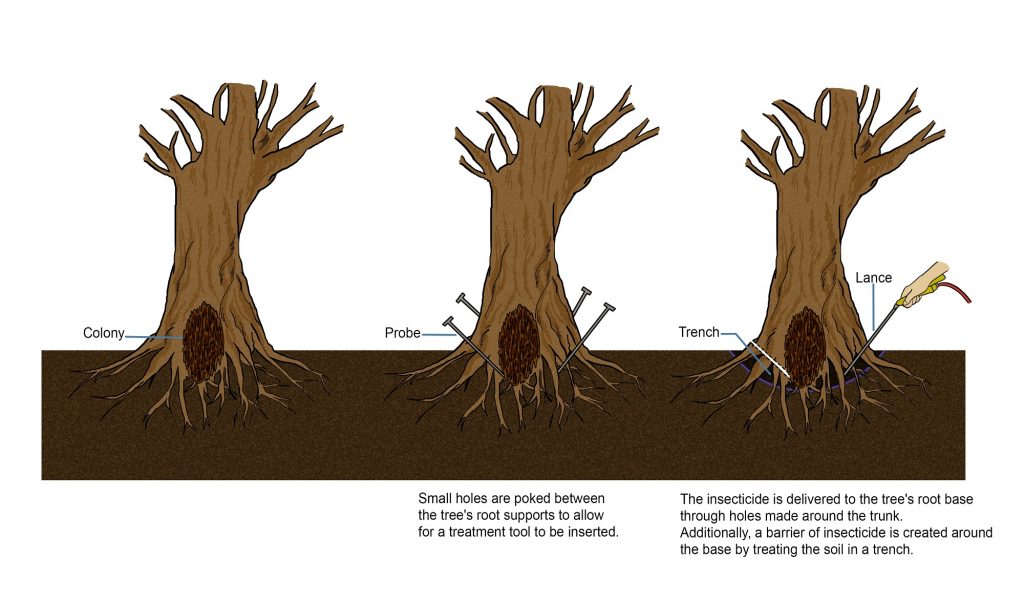

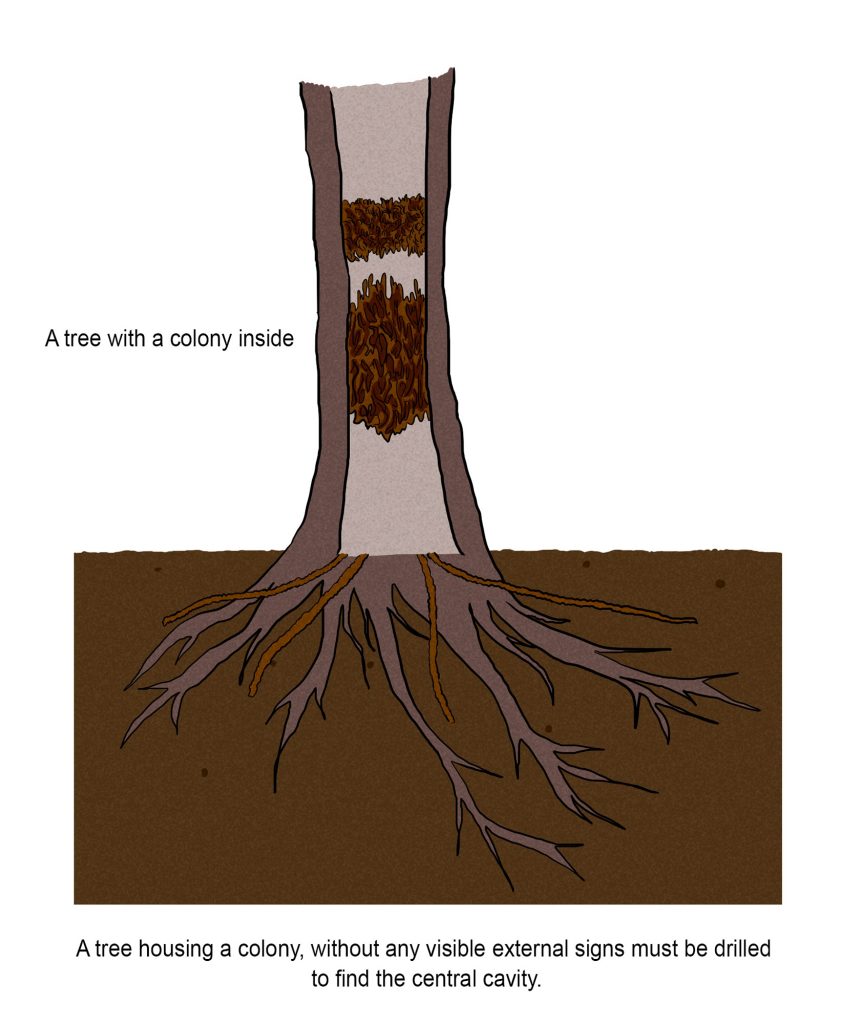

Several termite species dwell inside trees. They are particularly fond of older trees where the heartwood has deteriorated which creates hollow spaces for nesting. These trees should always be examined for potential termite activity

When a pair of termites manage to colonise a hollow tree or stump they have a high chance of thriving. These environments provide abundant food, a reliable source of moisture, and protection from humans, insects, and other animals.

The most destructive termite species in Australia dwell in trees. They are: Coptotermes acinaciformis, Coptotermes frenchi, Schedorhinotermes intermedius, and Mastotermes darwiniensis, although they don’t always nest in trees. Possible methods for detection and treatment include the following:

A root crown nest

Signs of a root crown nest may include mud packing at the base of the tree and flight slits in the trunk or branches. To confirm its presence, insert a metal probe downward toward the centre of the crown below ground level. Once the probe breaks through the soil into the nest, stop pushing with force. Carefully continue inserting the probe, feeling for a crumbling resistance as it moves through the carton-like nesting material.

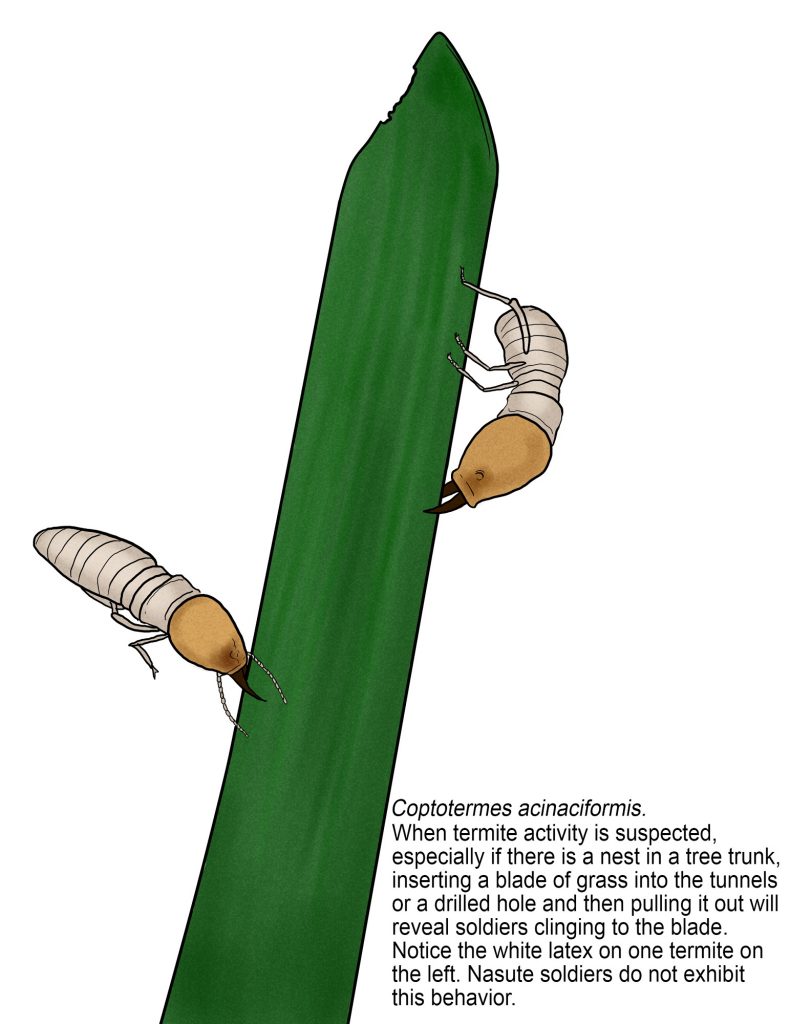

Observing the angle and distance of the probe’s entry into the nest from various points around the tree helps determine the nest’s size. The probe might feel slightly warmer at the tip due to the nursery area’s temperature, which varies with the ambient conditions. Termite inspections in trees involve creating a small hole in the trunk and inserting a long piece of grass. Leaving the grass in for 30 seconds and then slowly remind it can reveal termite soldiers clinging to it (except for nasute soldiers, a specific type with weak jaws(. This method might miss high nests near the base of the trunk, and hard ground can make it impractical. Treatment options for termites in trees are similar to those used for termite mounds. Additionally, creating a chemical barrier by injecting insecticide into the soil around the base of the tree can be helpful, but only if feasible.

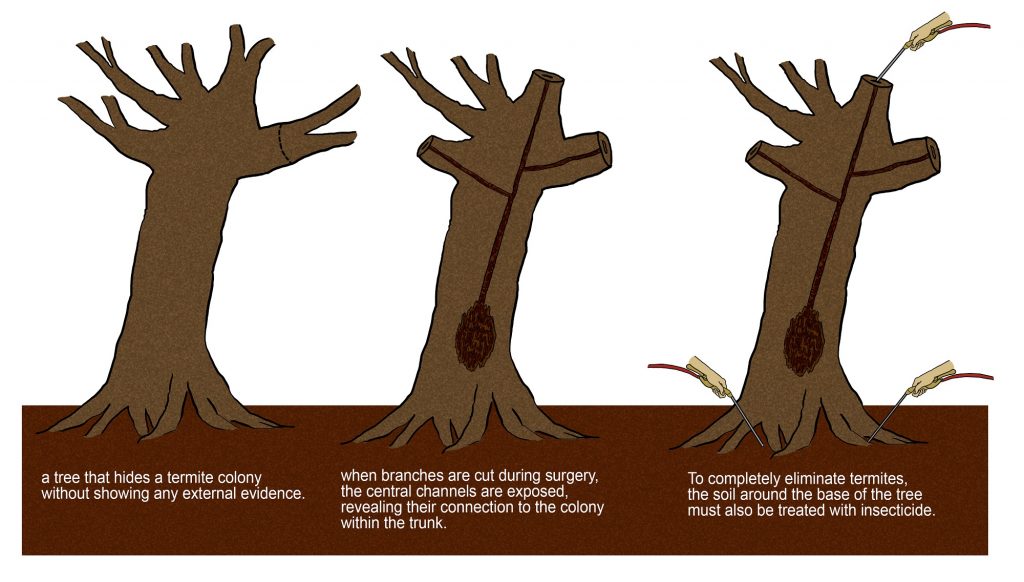

A tree trunk nest

For homeowners concerned about termites, inspecting trees for signs of infestation is important. Older trees with decayed centres are prime targets. Looking high on the trunk or branches for small slits, created by termites during swarming and later sealed. On smooth bark, healed-ver slits might appear as bumps. Broken branches with mud packed inside and dead branches revealing termite tunnels are also a cause for concern.

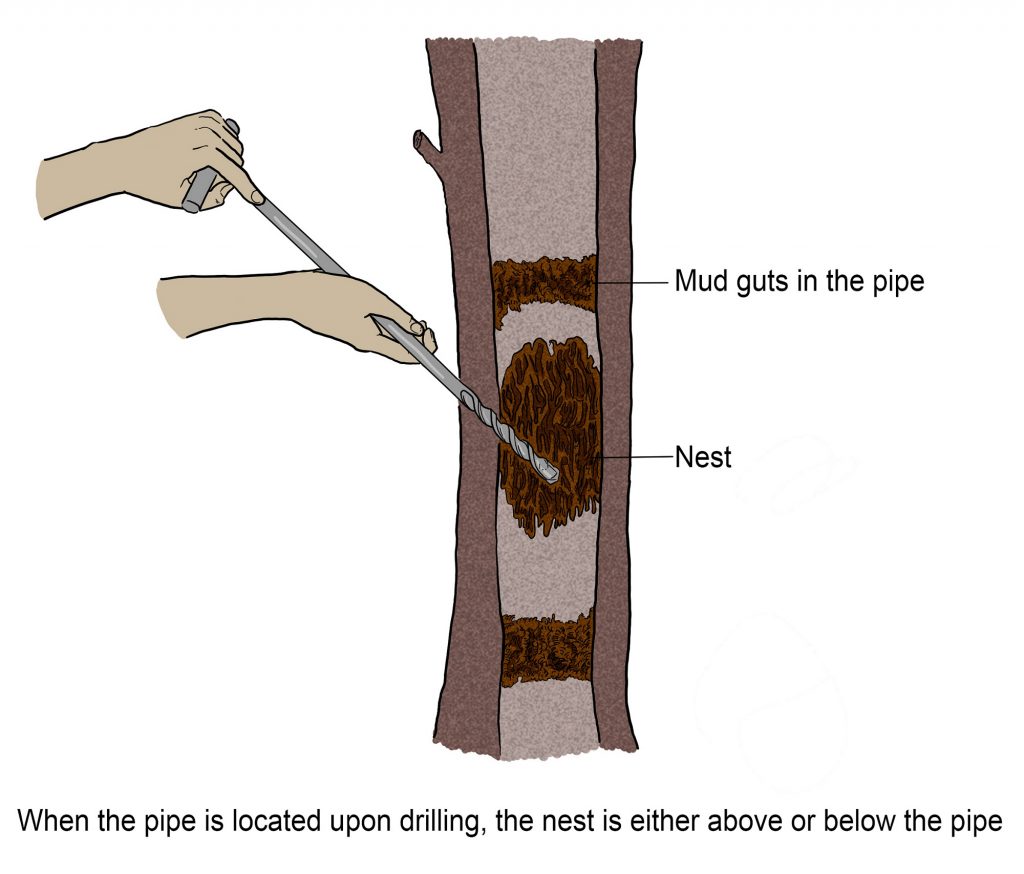

Locating nests hidden inside pipes requires a specialised approach. Start by drilling into the pipe at an angle towards its centre using a long, thin auger bit (10-15 mm diameter). As you drill, pay close attention to any sudden decrease in resistance. This could signal breaking through into the hollow core of the pipe of the nest itself. The feeling while drilling through the nest material will be slightly different – a less resistant sensation compared to the outer pipe. The colour and texture of the material extracted by the auger can also provide valuable clues. By combining these methods, pest control professionals can effectively pinpoint the location of nests within pipes.

Nests can be found anywhere along the pipe, from the root crown area up to the branches. However, they are typically located in the lower 1 to 1.5 metres above ground level. This is because the pipe is usually wider at the bottom and closer to the moisture source near the ground.

Chemical treatment options are similar to those used for mounds, including creating a soil barrier around the tree.

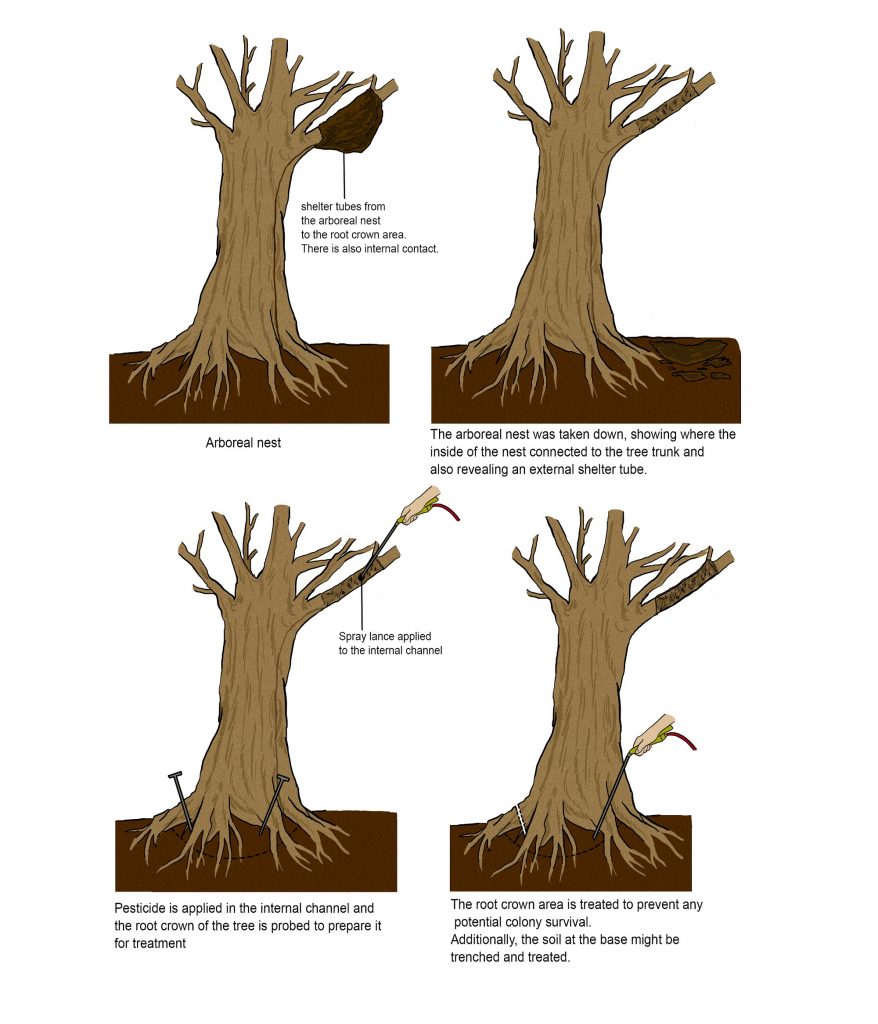

Arboreal nests

These nests connect to the ground through mud-covered tunnels, which often run along the tree’s exterior and sometimes through its central core. These insects usually prefer trees that are already in decline, and by the time their colony has grown large, the tree may already be dead. However, the colony will persist, continuing to inhabit and consume the wood.

For nests that are high and difficult to reach, isolate the termites within the tree by chemically treating the soil and removing mud leads from the tree’s exterior. Then follow these steps:

- Treat the root crown by applying termiticide directly to the soil surrounding the base of the tree trunk.

- Dig a trench around the base of the tree, refill it with treated soil, and ensure thorough watering to maintain the chemical barrier.

For accessible nests, the process involves:

- Whenever possible, physically remove the exposed nest and break it apart. This allows predators to eat the termites and help control the infestation.

- Identify and inject termiticide into the tunnels or holes where termites enter the branches or trunk, typically located at the point where the nest attaches.

- Probe the soil surrounding the base of the tree and apply termiticide directly to the crown area.

- Apply a barrier treatment around the base of the tree using the same method as for inaccessible nests.

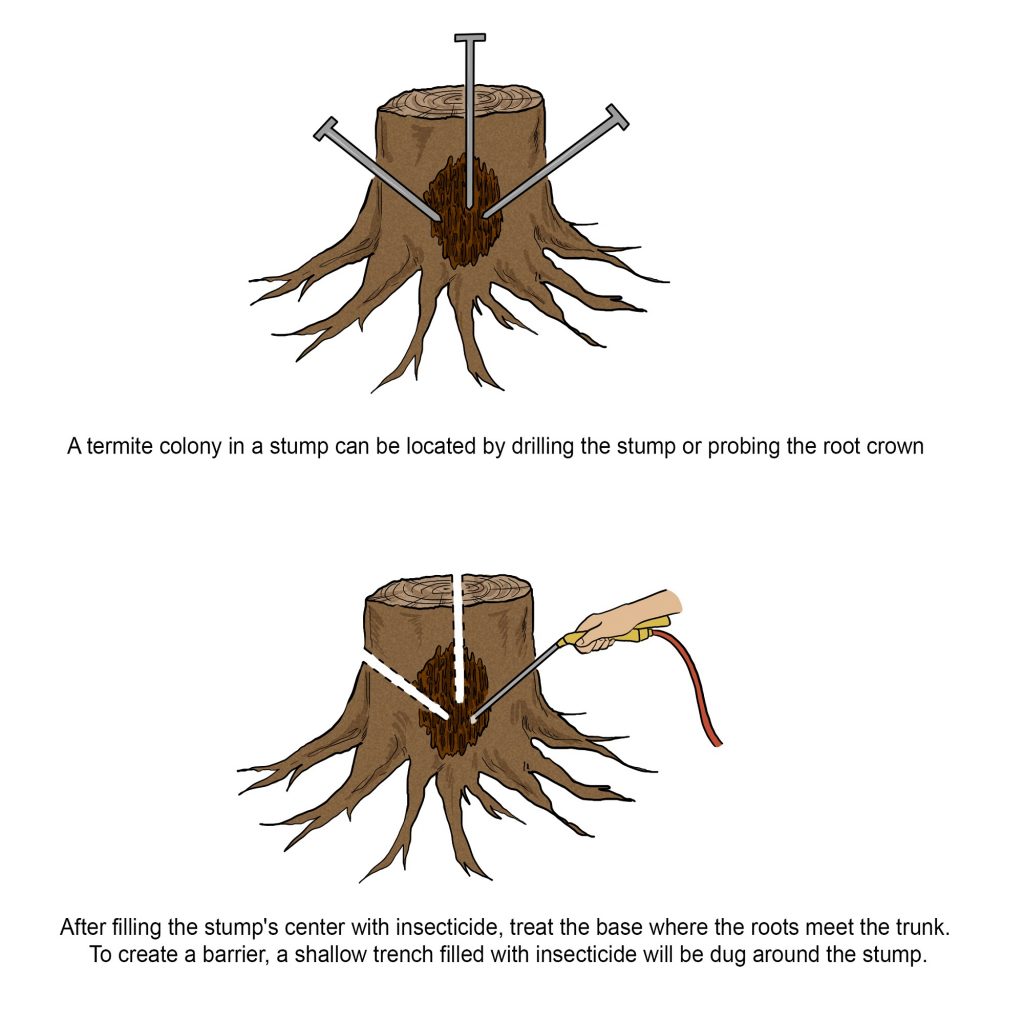

A tree stump nest

A tree stump has a high likelihood of housing termites since these economically significant pests prefer dead wood over living trees. In a stump, colonising de-alates can easily access a large amount of wood in direct contact with the soil. By enlarging a crevice in the stump or the of the gap between the stump and the soil, the pair can protect themselves from predators like ants and lizards by morning. Once the colony is established, pud packing often appears in the crevices at the top, sides, and the base of the stump.

Tree stumps are prone to termite colonisation and should generally be removed. However, some stumps are large, inconvenient, or expensive to remove, so homeowners often choose to use them as garden features. Adding tabletops, seats, plant pots, or vines can make termite detection more difficult.

Treating the stump can extend its decorative life. If the central core has deteriorated, drilling or probing can allow the insecticide to be flooded into any nests in the root crown area or contaminate the soil beneath the crown. Drilling at the base of the stump might reveal termite activity; if so, injecting insecticide into these holes will kill the colony and act as a soil contaminant to prevent further termite attacks, creating a trench and backfilling around the base will also help preserve the stump.

A nearby termite aggregation close to trees should be seen as an early warning indicator of another potential colony.

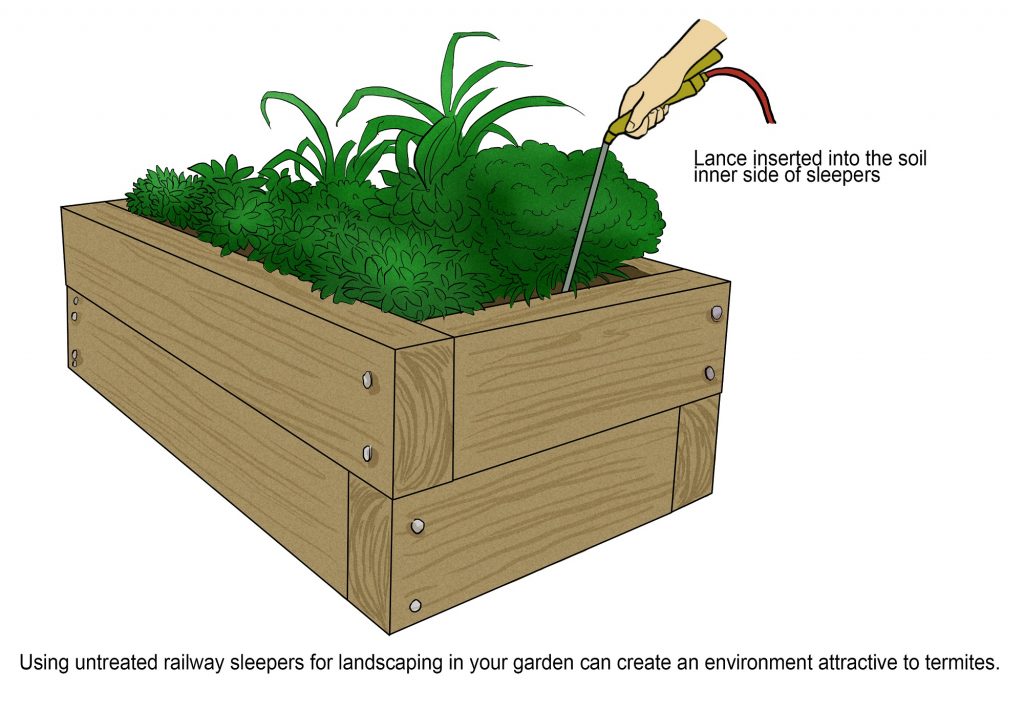

Colonies in railway sleepers used for landscaping

Untreated wood commonly used in landscaping like railway sleepers creates a perfect haven for termite colonies. While homeowners might mistakenly rely on short-term deterrents like engine oil, a thorough inspection is crucial.

Regularly inspect retaining walls, even masonry ones, as construction debris like timber offcuts can attract termites. Mud-filled crevices in timbers can indicate termite activity. Tapping the timbers can reveal hollowness, suggesting a need for further investigation and treatment.

Masonry walls also need checking for hidden termite activity. If termites are found, a special contaminant should be introduced before using liquid barriers or flooding treatments. While injecting insecticides can extend the lifespan of the wood, it might not eliminate all termites.

To ensure long-term protection, termite aggregation devices should be installed to monitor and treat any persistent colonies.

Locating and controlling active dampwood termites

Dampwood termites need moisture, which they primarily get from soil, trees, or damp stumps. Controlling these termites involves treating their locations and, if needed, the surrounding soil. Treatment is applied to various specific sites, such as:

Stumps

Inspect and probe their nests, then saturate them with a termiticide.

Poles and posts in the ground

Inspect both the pole and the soil around it and thoroughly saturate the holes with termiticide.

House

Eliminate any contact between the termites and the house’s wood, enhance ventilation where possible, and establish an unbroken chemical barrier.

Trees

Dampwood termite activity is frequently discovered during tree surgery. Carefully apply termiticide into the exposed tunnels, ensuring to avoid external contamination. Remove any loose material and seal the exposed area with urethane foam or a caulking compound, before sealing, the area can be treated with a fungicide to prevent internal decay.

Locating and controlling active drywood termites

Drywood termites, unline their subterranean cousins, don’t require constant moisture to survive. In Australia, these termites are often found during tree work or after trees are cut down. They target weak spots like old injuries, fire scars, and branch stubs left behind by fallen branches these termites can also infest posts, poles, and even tree stumps in the ground. While they don’t necessarily need ground moisture to thrive, some levels of moisture, such as high humidity, seem to be beneficial for them.

Cryptotermes primus (Australian species) and Cryptotermes brevis (introduced) are drywood termite species that attack timbers in many forms. Cryptotermes brevis is very cryptic as it can infest very small pieces of wood.

There are two categories for controlling drywood termites:

In trees

These species are often found during tree surgery or removal. Identifying them to the genus level is crucial to avoid unnecessary and costly soil treatments. Insecticidal treatments applied directly to the exposed galleries can be somewhat effective, eliminating the termites they reach. After treatment, sealing these surfaces can help prevent water from entering.

In buildings

The West Indian drywood termite (Cryptotermes brevis), was unintentionally introduced in Australia (Queensland, and later NSW). Australian quarantine officials took quick action to control and eradicate this pest from infested buildings. Buildings were entirely covered in plastic sheeting, meticulously sealed at the ground with sand to prevent any escape. Then, a powerful fumigant, methyl bromide, was pumped inside at a concentration of 1.5 kg/ 100 m³ of space for a full 24 hours. This intensive treatment aimed to eradicate all termites within the structure.

As of present, methyl bromide is no longer being used in the treatment for Cryptotermes brevis, and will soon become unavailable. Some countries use desiccant dusts of silica aerogel. In countries where C. brevis is well established, the use of pretreated wood and fumigation are the only effective control options.

Small articles of wood that are infested with C. brevis can be fumigated, heated, or placed in a sizeable freezer for more than 24 hrs.

Different Pesticide Treatments and Techniques to Eradicate Active Termites

Australian law mandates that any product claiming to modify behaviour or control pests must be registered with the Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority (APVMA) and labelled according to their standards. This includes adhering to label conditions, directions, and safety precautions. Essentially, pesticides not registered for termite control cannot be used for that purpose. Most manufacturers have decided to limit the use of most termite control products to licensed pest controllers.

The Australian standard mandates that efforts be made to treat active termites before beginning any soil barrier treatment treating active termites is worthwhile because if successful, it eliminates that damaging colony. However, the effectiveness of applying a new continuous chemical soil barrier cannot be fully guaranteed. The main access shelter tube through the soil into a building can be thick-walled and resistant to insecticides applied to the surrounding soil techniques like trenching, rodding, drilling, and flooding under concrete do not always penetrate or disrupt this main access tube.

Efficacy of the treatment

The efficacy of dust treatments depends on these factors:

Time of year

Termite dusts work best when termites are actively foraging, which typically happens in warmer months. Winter treatments might not be as effective due to reduce termite activity.

Operator Skill

Termite dust treatments are a powerful tool, but they require specific knowledge to use effectively. Identifying the termite species is crucial to choosing the right dust, and applying it correctly takes practice. Basically, you need to be a termite expert and a pro at dusting to get the job done right.

Moistness of workings

Termite dust needs dry conditions to spread throughout their tunnels (galleries). If the galleries are moist, the treatment likely won’t work. This means checking the moisture levels before applying dust treatments. Focus on dry areas for best results.

Technique

During termite dust applications, it is crucial to avoid overfilling the dust blower bulb, as it should mostly be filled with air. Clumps of dust can obstruct termite tunnels and galleries. This blockage can force termites to avoid treated areas or even seal them off entirely, reducing treatment’s effectiveness.

Species treated

Different species respond better to specific treatments. Dust applications, for instance, are not effective for all termites. Here’s what to keep in mind:

- Multi-nester termites have scattered colonies, so dust only reaches the ones it directly touches, potentially missing hidden ones.

- Nesting habits of drywood and dampwood termites make them hard for dust to penetrate.

- May termites are more susceptible to liquid insecticides. These can be sprayed on them or directly into the nest for better control

Warranty

Dust treatments for termites can be tricky; they might not always work because they may not reach all the other nests that may exist. This is especially true if there are other nests nearby that can’t be treated because they are on a neighbour’s property. To get long-term protection for a house or building, a chemical soil barrier treatment is a better option. This creates a zone around the property that keeps pests out.

Foams

Insecticide foams are a new tool for termite control. They work well when used with termite detection methods like thermal cameras, which can pinpoint termite activity in walls. Once a termite mass is found, a small hole is drilled into the wall cavity. The insecticide foam, either from a spray can or mixing machine, is then injected into the cavity. This foam expands quickly, filling termite tunnels and reaching hidden areas. After expanding, the bubbles break leaving a damp residue containing the insecticide on the termites and surfaces. While foam itself won’t directly kill the termites, it coats them, and the area they’re in. This contamination is then spread throughout the colony as the termites move around, ultimately killing them off.

Insecticide foams are a versatile tool for termite control beyond wall cavities. They can be injected directly into damaged wood, like architraves, skirting boards, and heavily infested framing timbers. Foams have also shown success in treating large, above-ground termite nests. However, they are not recommended for use in mud tunnels due to the material’s absorption properties. While directly applying foam to termite mounds or nests in trees is usually effective, for faster and potentially cheaper results, consider using instant-kill liquid termiticides.

Gels, granules and pastes

Termite control does not stop at liquids. Gels, granules, and pastes offer another way to fight termites, especially around aggregation points where termites gather. Unlike dusts and foams that fizzle out quickly, these long-lasting options act like bait. They tempt worker termites to take the bait, literally, by providing an alternative food source to the cellulose they’re harvesting. This approach has proven to be effective for many years.

Liquid insecticides

If a colony in a tree is found, a short-lasting insecticide can be used to kill the entire nest. This is a good option for both pest and non-pest termite species. However, the effect of this treatment only lasts a short time. The treated tree will eventually become attractive to other termite colonies searching for a new home. So while, this method gets rid of the current termite problem, it does not prevent future infestations.

Most insecticides effectively kill active termites due to their soft bodies and vulnerability when sprayed. However, only insecticides specifically registered for termite use, as indicated on the label, can be used by professionals or homeowners. Non-compliance with the label instructions can result in penalties.

For treating termite colonies, liquid insecticides are typically applied using a mechanical pump at low pressure. Large volumes of 20-40 liters per nest, depending on the size, are generally required. Nozzles that deliver a high volume of liquid rather than producing fine spray droplets are preferred.

When drilling holes into tree trunks, stumps, or mounds for insecticide application, it is important to drill at a downward angle. This ensures that gravity aids in delivering the insecticide into the nest, making the process more effective.

Contaminant dust

A dust treatment is applied directly into nests using a dust blower. It is slow acting and does not take effect immediately, which gives the workers enough time to spread the contaminant to as many colony members are possible. The more galleries or termites dusted, the more likely it is for the treatment to be successful. After the treatment, worker termites carry the dust on their bodies and back to the colony. The contaminant dust is passed on to other colony members while they are using the tunnels and when they groom each other. Termites are also cannibalistic and will eat dusted and poisoned termites, and may result in secondary poisoning but the death of the colony primarily depends on their grooming behaviour.

Dusting techniques

The most popular and effective apparatus used for dusting is a hand-held dust blower with a rubber bulb and a thin metal tube. For large structures such as trees, bridge girders, etc., motorised dust blowers are used.

The bulb of the hand-help dust blower is only filled with a quarter of the dust mixture. This ensures that very little dust will be discharged when the bulb is gently squeezed. The more air discharged with the dust, the further the dust travels to lightly cover the tunnels. The aim is 90% air and only 10% dust.

Successful dust treatments start with carefully opening up the wood and mud packing to gain access to the galleries. This requires the technician to be very gentle and unhurried so that active termites would not be disturbed and they would keep picking up and spreading the dust contaminant every time they pass through the tunnels and get in contact with other colony members after the treatment.

Termite aggregation devices

Termite control often uses a technique called termite aggregation. This means getting a lot of termites together in one spot. This minimal disruption is done so their natural behaviour continues. They’ll keep sharing food, grooming each other, and doing other termite activities. The key is, that they will also be sharing the treatment that was applied. This way, the poison gets carried back to the nest by the worker termites. It will then spread to the juvenile termites, soldiers, alates, and even the king and queen termites. By targeting the entire colony, termite aggregation helps us eliminate them effectively.

Termite control goes beyond just protecting the property. Since termites come from outside, reducing the number of colonies around the property can significantly ease the pressure on termite barriers, saving money in the long run. These barriers, whether physical or chemical, represent a big investment. Experts estimate that over 95% of termite infestations originate from outside the house. By placing monitors around the property, there’s a much higher chance of catching termites before they reach the property.

In the past, pest control relied heavily on chemical barriers like dieldrin and chlordane. These chemicals could be applied to the soil around a house and would last for many years, creating a protective barrier. This led to the idea of building “fortress homes” that were sealed up tight and surrounded by a treated soil zone. However, this approach has some drawbacks.

Termite colonies are everywhere in Australia – chances are there’s one within 23 metres of most houses. These colonies can be young and short-lived, but if they survive, they can grow into major threats. Homes rely on chemical and physical barriers to keep them out, but all it takes is one weakness for a termite problem to start. These hidden colonies are constantly searching for ways to exploit gaps in home’s defences.

Termite treatments are a big part of a pest controller’s job because the initial termite barrier often fails. To truly protect a home, pest controllers need to offer termite monitoring and baiting systems. These target any nearby colonies that might try to attack the house again.

Another issue is homeowner behaviour – by the time a technician arrives, the homeowner has often disturbed the termite activity. They might tear into walls or move objects, making it harder to place termite bait or spray effectively. This disrupts the termite activity and makes it harder to eliminate the colony.

The key to wiping out a termite colony is maximizing the number of termites exposed to the treatment. The more workers that carry the insecticide back to the nest, the higher the chance of eliminating the entire colony. However, locating the nest is often difficult. So, while attracting termites to a central location (aggregation) can be helpful, it only works if the treatment doesn’t disrupt the termites after they gather. If the insecticide stops them from acting normally and carries them back to the nest, then attracting a large number won’t be effective. Therefore, there are several important factors to consider when choosing and using termite aggregation devices.

Attraction

Termites weed on moist cellulose, which is why cardboard and paper are easy targets. However, these materials can rot quickly in damp places. When that happens, they release carbon dioxide, like a dinner bell for termites nearby. Adding cardboard to wood won’t make it any more attractive to termites than wood alone. But for fast-eating Mastotermes species, some extra wood can keep them feeding in the area for a bit longer.

Termite access

When installing termite monitoring devices, ensure entry holes from the soil are at least 4mm wide, ideally 8mm. While termites can tunnel very deep, most activity occurs in the top 15cm of soil. This larger opening allows easier access for the termites and improves the effectiveness of the monitoring device.

Size

Termite bait effectiveness increases with the number of termites it can attract and eliminate. Small bait stations like wood blocks or ice cream containers hold fewer termites compared to larger ones. A larger station containing more termites (think 6 litres compared to 2) will provide effective treatment. As long as these larger stations remain undisturbed by the termites, they are much more likely to completely eliminate the colony.

Ease of introducing the treatment

The key to successful termite baiting is minimising disturbance during installation. We want to achieve two main goals. First, enough termites need to be exposed to the bait so that some contaminated food gets carried back to the nest. Second, the bait station needs to be introduced in a way that doesn’t disrupt the termites’ foraging routine. This ensures a steady stream of worker termites returning to the station over the following weeks, continuously harvesting and sharing the bait with the colony.

Siting

Termite monitors should be placed strategically to maximise their effectiveness. Priority areas include:

- Any past termite activity on the property – yards, outbuildings, fences, retaining walls, trees, or the house itself. Monitors near these areas will detect termites quickly.

- Neighbouring properties with known termite problems. Placing monitors close to shared property lines with termite-infested neighbours can help identify infestations early.

- Trees with hollow centres. These trees are particularly attractive to termites and warrant close monitoring.

Effective termite monitoring requires strategic placement of aggregation devices, avoid placing them near existing chemical barrier treatments, which typically extend up to 30cm from the foundation. Ideally, position devices 40-50 cm away from the building to ensure they attract termites without interfering with the repellent effect of the chemical barrier.

Moist areas are prime locations for termite activity. Garden beds are excellent choices for placing devices due to the consistent moisture they retain, making them attractive to termites.

Do not limit deployment to the exterior. For suspected infestations entering through cracks in concrete floors, often found in commercial buildings, use a long, large device positioned directly over and along the crack to capture termites attempting to enter.

Preventing attacks from subterranean termites

Termite problems have plagued Australians since the early days of European settlement. From the moment those first settlers in Port Jackson saw their tent poles and buildings crumble, Australians have been looking for ways to protect their structures from these destructive insects. This has led to the development of various techniques, including barriers and specific construction methods, to keep termites at bay.

Termite inspectors constantly encounter stories of these determined insects breaching even the most well-thought-out defences. While various methods have helped reduce termite attacks, a combined approach is essential for success. Here’s why. Tiny gaps caused by construction choices, landscaping changes, or even burrowing animals, can become entry points for termites. Additionally, in buildings with timber frames, all the wooden components are interconnected, creating a network for termites to travel and cause widespread damage. This emphasizes the importance of preventative measures during the design phase of construction (though this won’t help existing buildings). Such preventive measures are discussed below.

Design

Termites are less interested in buildings made from steel, glass, and concrete. They might still be attracted to things inside like furniture, books, or anything with cellulose that isn’t moved often.

Treated timber with low-risk insecticides is becoming available, and these treatments can last over 20 years.

A company providing professional indemnity insurance to the pest management industry reported that 99% of claims involve slab-on-ground construction, while only 1% involve buildings with suspended wooden floors. This is because pest controllers can easily spot termites in crawl spaces by following the mud tubes they build.

Use of physical barriers

The Australian Standard mandates termite protection for all buildings. This is achieved partly through physical barriers that stop termites from entering. These barriers act as a doable defence: first, by physically blocking their way in, and second, by showing clear signs of an attempted breach. If termites try to cross the barrier, they will leave mud tunnels as evidence, making detection during inspections a breeze. The standard outlines three types of physical barriers to choose from depending on the situation:

Metal or other impenetrable capping

Metal caps are a common tool for spotting termites. They are typically placed on top of foundation piers or stumps. They are also found along foundation walls and staples in older buildings. These caps are important because they force termites to reveal themselves. Normally, termites entering wooden or stone piers can travel undetected inside. Butt when they hit the metal, they have to build many shelter tubes to go around it. These tubes are easy for inspectors to spot. There’s one important thing to remember during installation: do not nail or spike the caps to the wood. Over time, the nail hotels can rust and create gaps that termites can sneak through.

These barriers can be made from different types of metal and are installed on walls of foundations, they have a lip that sticks out at an angle at the bottom to stop termites from climbing over. But even if the lip is angled at 45 degrees or more, termites can still build mud tubes over it to bypass the barrier. This means the metal barrier needs to stick out far enough that termites have to build their mud tubes entirely on the outside of the barrier for them to reach the wood. If the termites build these tubes, it’s a clear sign that they are trying to get into the building and that you need to take action.

Termites can enter through openings in pipes, wires, and cables that go into the foundation. To stop them, metal shields are supposed to be installed around these openings.

The problem is, that these shields are often put on wrong during construction and aren’t checked properly later. Homeowners rarely inspect under their house, so they just assume the shields are working, which can be a big mistake. Basically, these shields can’t be trusted unless you inspect them yourself.

Stainless steel mesh barriers

Termite mesh barriers work by using very fine mesh that blocks termites from entering the building. It is important to use the right type of stainless steel for this mesh, as lower grades can rust. When installed properly according to the Australian Standards, this barrier creates a long-lasting shield for your building.

Finely divided aggregate barriers

Experts studied crushed rock as a barrier against these destructive insects. In Hawaii, they tested finely ground basalt (1.7-2.4 mm particles) against the Formosan termite (Coptotermes formosanus). The size proved effective because the termites could not move the particles or squeeze through the gaps. Australia saw similar success with crushed granite for the same reasons. These crushed rock barriers are most useful during construction, especially for slab-on-ground foundations, and can also be applied to existing buildings. For specific details on using crushed rock termite barriers, refer to the to the Australian Standard.

Use of chemical barriers

Subterranean termites live underground and build their nests in the soil. To find food, they create tunnels that branch out from the nest. If they find a food source above ground, live wood in a building, they can build mud tubes. These tubes act like protective tunnels that allow the termites to travel up walls and foundations without being exposed. Once inside the building, they can chew through drywall, panelling, and other materials to reach the wood, often going unnoticed.

One way to stop termites from reaching a building is to create a chemical barrier in the ground. This involves applying an insecticide around the foundation of the building, creating a zone that termites won’t be able to cross. This method essentially isolates the building from termites.

Two types of termiticides exist for soil barrier treatments: deterrent and non-deterrent. Deterrent termiticides create a zone around the building with a detectable residue. This residue either repels termites or kills them upon contact, preventing them from breaching the barrier and reaching the structure.

Non-deterrent termiticides, on the other hand, don’t repel termites. However, as termites move through the treated soil, they pick up the insecticide on their bodies. This can be fatal to them and may even be carried back to the nest, killing the queen, nymphs, and ultimately the entire colony. Proponents of the non-deterrent termiticides argue the “carry-back effect” eliminates surrounding termite populations, reducing pressure on the barrier and potentially extending warranty periods. However, it’s important to remember that these termiticides rely on termite contact and may not reach all nearby colonies, leaving them free to continue attacking unprotected wood sources.

Chemical barriers come in two main forms: liquids and sheets. They create a bug-killing zone around your building’s foundation. This zone can be made of treated soil, a specific depth and thickness, or a special sheet that keeps water out and termites away.

These barriers are usually installed before the foundation is even built, following Australian Standards. But if termites find a way in later, or chemicals in the barrier weaken over time, reapplication of the liquid treatments is an option.

Liquid application

Liquid termiticide are most effective when applied during different stages of construction. Before laying the foundation, the soil around the building will be treated with a specific amount of termiticide. This mount depends on the type of soil. The termiticide is applied by soaking the ground to create a barrier that will prevent termites from entering the structure.

Perimeter chemical barriers are a crucial part of post-construction termite control. This method involves creating a trench around the building’s foundation and flooding it with termiticide. This creates a chemical barrier that prevents termites from entering the structure. For optimal results, the trenching and treatment should be done after the building is complete and grading is finished. However, it is important to perform this step before laying patios, walkways, or driveways. Paving stones are preferable to concrete in these areas because they can be easily lifted for future retreatment. Concrete, on the other hand, requires drilling, making it difficult to re-establish a continuous termite barrier if needed.

Australian Standard(s) require both underfloor and perimeter treatments for a complete termite barrier. Skipping either element compromises the overall termite protection for the building.

Reticulation systems

Reticulation systems are a great way to provide long-term pest control. These systems use a network of pipes installed underground around the building before the foundation is poured. The pipes have outlets for applying treatment later on. There are a couple of things to keep in mind: Over time, the soil can settle and leave gas around the pipes. This can happen when sand used for levelling before pouring concrete moves. These gaps can be filled during retreatment, but it’s important to be aware of them. The perimeter system can be installed under walkways or even around the entire building, but be careful with using large gardening tools near the perimeter as they could damage the pipes if they aren’t protected. Reticulation systems can also be used for buildings with crawl spaces, and can be installed used existing structures.

Termite barrier sheets/membranes

This method uses special sheets with built-in termite protection. These sheets are laid down before pouring the concrete floor of a building, following the Australian Standard and Building Code of Australia. Only licensed professionals can install them. The good news is these sheets are easy to handle and come in different sizes to fit around the foundation, utility openings, and other areas. The amount of termite fighter in the sheets stays consistent, and you can easily check for gaps before pouring concrete. Studies suggest these sheets may protect a building from termites for over 50 years.

Existing buildings

When termites invade a building, eradication methods become necessary. This means the existing termite barrier, if there was one, has been compromised. In these cases, pest control companies will re-apply a chemical barrier treatment around the foundation. However, it’s important to remember that these treatments usually don’t come with warranties and their main purpose is to prevent termites from re-entering the building, not necessarily eliminate the entire colony.

Moisture

Subterranean termites crave moisture, they need it to build and keep their colonies going. This moisture also helps grow fungus in the wood they eat for protein. While drying out the area under a building won’t completely stop them, it does make it a less appealing place to set up shop. Ventilation is key here as it helps remove moisture from the air and stops condensation from building up on the wood. Wire mesh vents are especially good because they allow plenty of air to flow through.

To effectively prevent subterranean termite infestations, managing moisture around the foundation is critical. Leaky pipes and drains create attractive havens for termites by providing essential soil moisture. These leaks should be repaired immediately. Similarly, air conditioner condensate should be directed to the building’s drainage system, and not allowed to drip onto lawns or foundations. In areas with high natural water seepage, consider installing subsurface drains. Finally, while maintaining healthy foundation plantings is important, overly moist soil near the building attracts termites. Encourage clients to maintain a drier zone next to the structure to deter termite foraging.

Removing surrounding wood

Termites are attracted to decaying wood, and leftover building materials can create prime spots for them to establish a colony. Untreated wood scraps and formwork left in the ground after construction provide a perfect food source. This is especially true for untreated railway sleepers used in garden beds. The combination of wood and a mixture in these situations creates ideal conditions for termite development and has been linked to many infestations. Avoid these attractants by removing leftover wood and using treated lumber for landscaping projects.

Landscape timbers like pressure-treated pine are great because they resist termites and last a long time. Utility poles are also pretreated and inspected to avoid termite damage. However, be on the lookout for termite problems behind retaining walls. These areas often become dumping grounds for wood scraps, stumps, and branches. Do not be fooled by a fancy retaining wall – termites can still be lurking behind it. Always check these areas for signs of infestation.

Removing dead trees and tree stumps

Tree removal does not always mean everything gets hauled away. Grinders might leave chunks of trunk underground, creating a perfect home for termites. These could be subterranean termites, the kind that live to tunnel, or dampwood termites that thrive in moist, decaying wood. Even the leftover roots become a termite buffet, attracting these unwanted guests.

Use of resistant timbers

While the use of termite-resistant wood in construction sounds ideal, it is not that important today. Price and availability are what builders choose most of the time. For areas with high termite risk, using pressure-treated wood or natural rounds can be reliable. However, be aware that termites can still build shelter tubes over treated timber to get to non-resistant wood. While pine timbers have a natural resistance to several species of the genus Nasutitermes, which prefer hardwoods like eucalypts, other species that target pine are usually nearby too.

Care with building additions and renovations

Adding features like patios, second floors, pergolas, or even kennels can bridge existing termite barriers, allowing access to homes and causing significant damage. Australian Standards for termite barrier installation and application should be followed during any construction to prevent this.

When houses change hands, information about existing termite barriers should be passed on to new owners. Homeowners may not be aware that these barriers degrade over time. If a property has a history of termites or is in a high-risk area, annual inspections are essential to catch problems early and minimize damage to structural timber and joints.

Termites Gallery