In order to fully understand insect pests, you will need to understand the morphology and functions of their body parts.

External Morphology

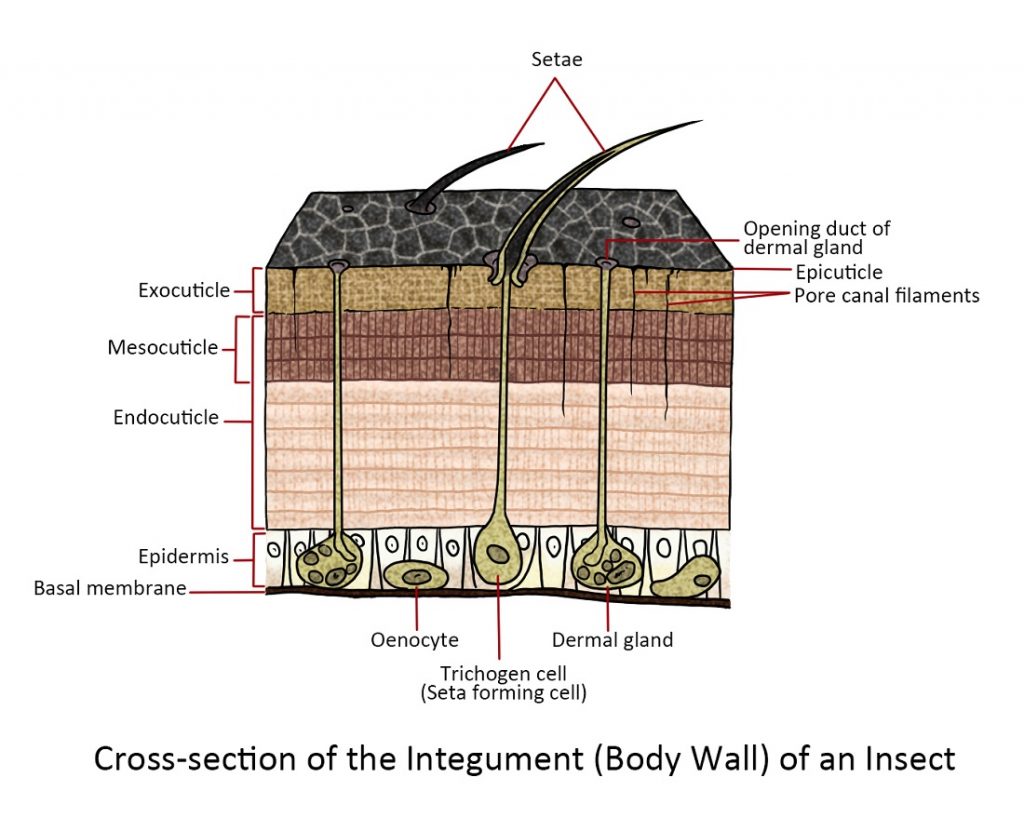

The Body Wall or The Integument

The integument varies from insect to insect in the degree to which it has been sclerotized or hardened. Termite workers and soldiers live in moist secluded nests underground and have a soft integument, whilst beetles that live a more exposed life have a thicker protective body wall.

The integument of an insect functions to:

- Protect the internal organs

- Provides an area for muscle attachment

- Protect insects from desiccation, injuries

The insect body wall is comprised of three layers listed from the outermost to the innermost layer:

The Cuticle is made up of two distinct main layers, namely, an outer primary cuticle or exocuticle and an inner secondary cuticle or endocuticle, while the exterior has a very thin waxy surface layer or epicuticle that is a clear borderline about one micron in thickness. The exo- and endocuticle’s main constituent is a polysaccharide carbohydrate called chitin, but the exocuticle contains other substances and is distinguishable from the endocuticle but its darker colour and it is denser since it contains the hardening substances that form sclerites. The epicuticle does not contain chitin, instead, it contains phenol-stabilized protein and is covered in a waxy layer comprising fatty acids, lipids and sterols.

The Epidermis is the outermost cellular layer of the insect. The epithelial cells are arranged in a single layer in most cases, but they may become separated into two layers or disposed irregularly. It is responsible for secreting a tough cuticle (mostly composed of fibres of chitin) and enzymes involved in dissolving and absorbing old cuticle.

The Basement Membrane is the basal part of the body wall located beneath the epidermis where the muscles are attached. It is thin, about 0.5 microns thick and is formed from the degenerated epidermal cells. It consists of fibrous protein, glycoproteins, collagen, etc.

The insect body is enclosed in the integument and as they reach adulthood they increase in size. Most insects moult or shed their cuticle periodically and produce a new and larger cuticle as they mature. To accommodate the short-term needs and functions of insects such as ingestion and locomotion the integument is not uniform in thickness and hardness. Instead, each plate of the exoskeleton is joined by a softer and more flexible cuticle that is underneath the harder plates. When the insect needs to expand, the more flexible cuticle is expanded out from the rigid plates.

To receive external stimuli from the body wall, the insects have developed certain epidermal cells into sensory projections, pits, or slits. An example of this is a seta or sensory hair protruding from the body.

Contact insecticides need to penetrate the insect cuticle for them to work, unless the insect’s eating or grooming habits permit the entry of the treatment orally. The waxy layer of the epicuticle inhibits the entrance of most insecticides and acts as a barrier. Sometimes the insecticide will gain entry through the tracheal system or other locations and travel laterally to the procuticle. The thinner membranous cuticle found between rigid plates also provides a barrier from insecticides.

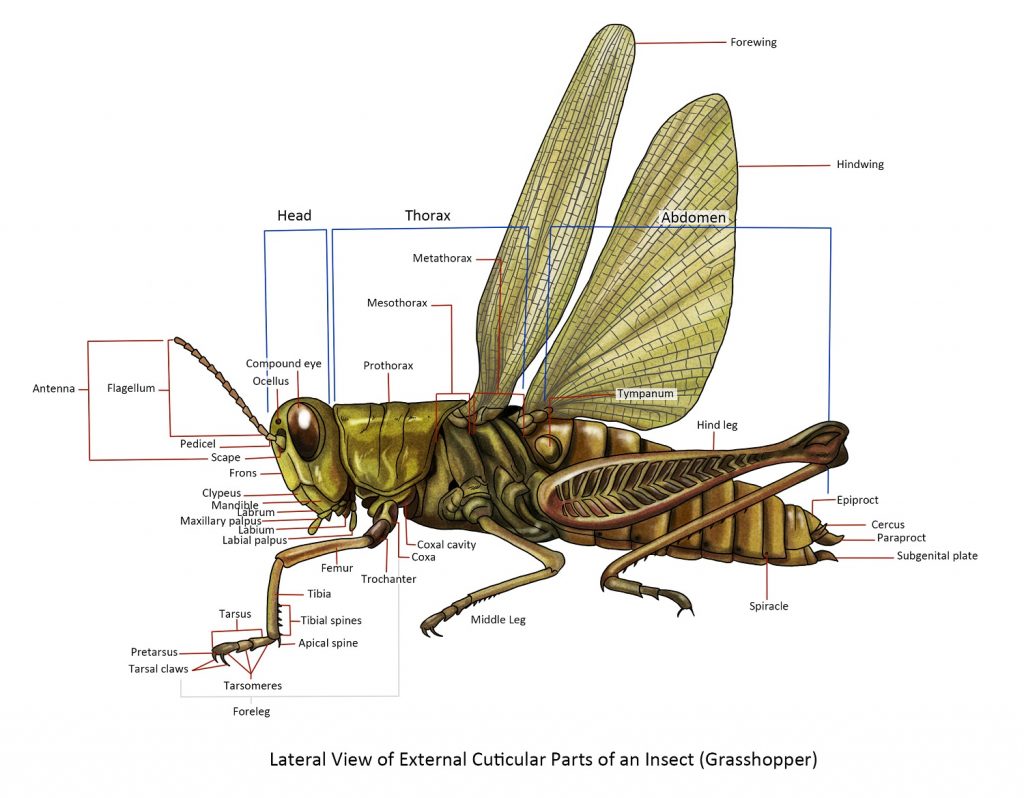

The External Components

The insect body is divided into three parts: the head, thorax and abdomen. The most accepted theory of the origin of insects is that they evolved from a segmented, legless, worm-like annelid stage. The worm-like annelid then grew pairs of lobe-like appendages and simple eyes. As evolution progressed, the creature fused the first five segments and appendages to form the head, mouthparts, and antennae. The next three segments formed the thorax, which kept the 3 pairs of appendages as legs and later developing wings. The creature lost appendages on segments to form the abdomen and the last segments and appendages were modified into the external genitalia.

Term used for orientation:

Anterior – relates or refers to or situated near the head or the end most nearly corresponding.

Posterior – pertains to the hind part of the body; the end most corresponding or situated behind.

Lateral – relating to the side of the body.

Dorsal – relates to or situated at the back

Ventral – pertains to the lower surface or belly of an animal or opposite the back.

The Head is the anterior body part of the insect and it contains the major sensory organs (antennae and eyes) and mouthparts.

Head Orientation

The orientation of the insect head varies with respect to the rest of the body. There are three insect head orientations:

The hypognathous head has the mouthparts directed downwards. This is thought to be a primitive condition. This is mostly seen in phytophagous or plant-feeding species.

The prognathous head has the mouthparts directed anteriorly and is found in carnivorous adult insects and in the larvae of beetles.

The opisthognathous head has the mouthparts directed posteriorly or pointed backwards between the front legs. This occurs in members of the insect Order Hemiptera.

Eyes

Compound eyes. The compound eyes of an insect are usually the large paired eyes on each of the head. Most adult insects have compound eyes but there are some that do not. The compound eye is composed of many identical minute units called facets or ommatidia. The compound eye allows the insect to see images in multiple directions and in a wider view than human eyes.

Simple eyes. There are two types of simple eyes:

Ocelli – Many adult insects that undergo an incomplete metamorphosis have two or three ocelli. They are usually located on the front of the head between the compound eyes. They function as photoreceptors or as sensors of ambient light intensity. Information from the ocelli can affect the development and behaviour patterns of the insect.

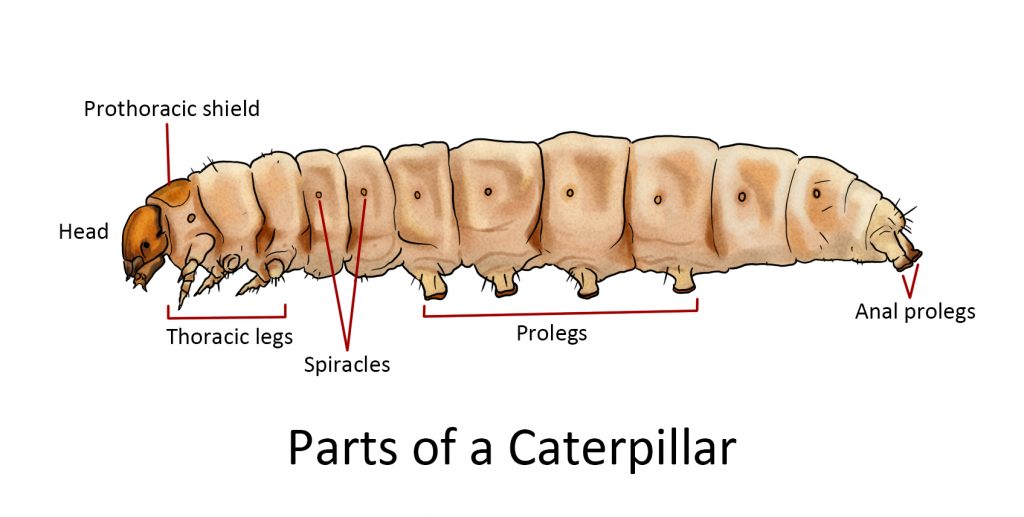

Stemmata – The juveniles of insects with complete metamorphosis (e.g. caterpillars, maggots) do not have compound eyes. Instead, they have stemmata, which function for spatial vision, spectral sensitivity, and motion perception.

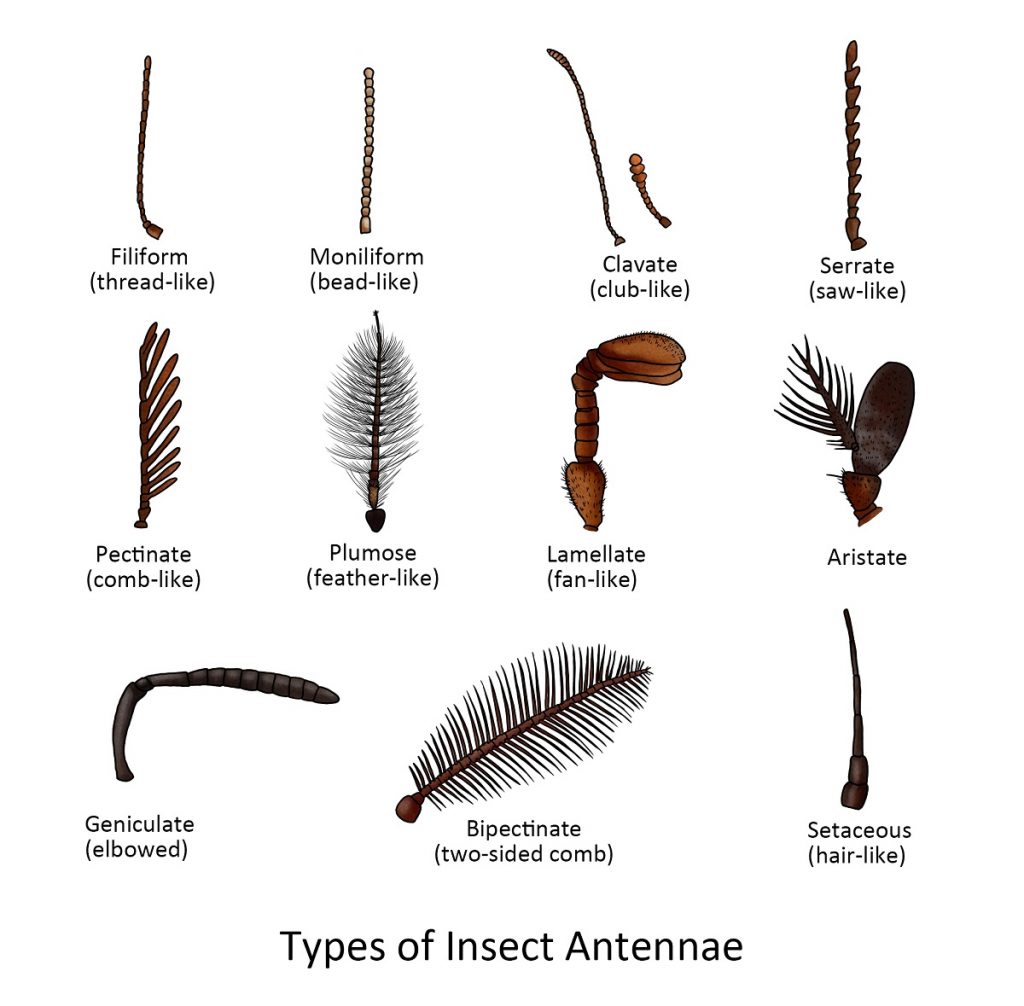

Head Appendages

The Antennae. The antennae are the first appendage of the head present in the adult insect. The typical insect antenna has many joints and generally has three parts: the scape, pedicel, and flagellum. The first part is the scape and it is the basal stalk by which the antenna is attached to the head. The second part is the pedicel — it is short in many insects and it bears a special sensory structure known as the organ of Johnston, which is used to detect vibrations and to find a mate. Beyond the pedicel is the flagellum or clavola (in lamellate or clavate antennae) — it is usually long and consists of many small subsegments, although it may be reduced to a single piece.

Types of Insect Mouthparts

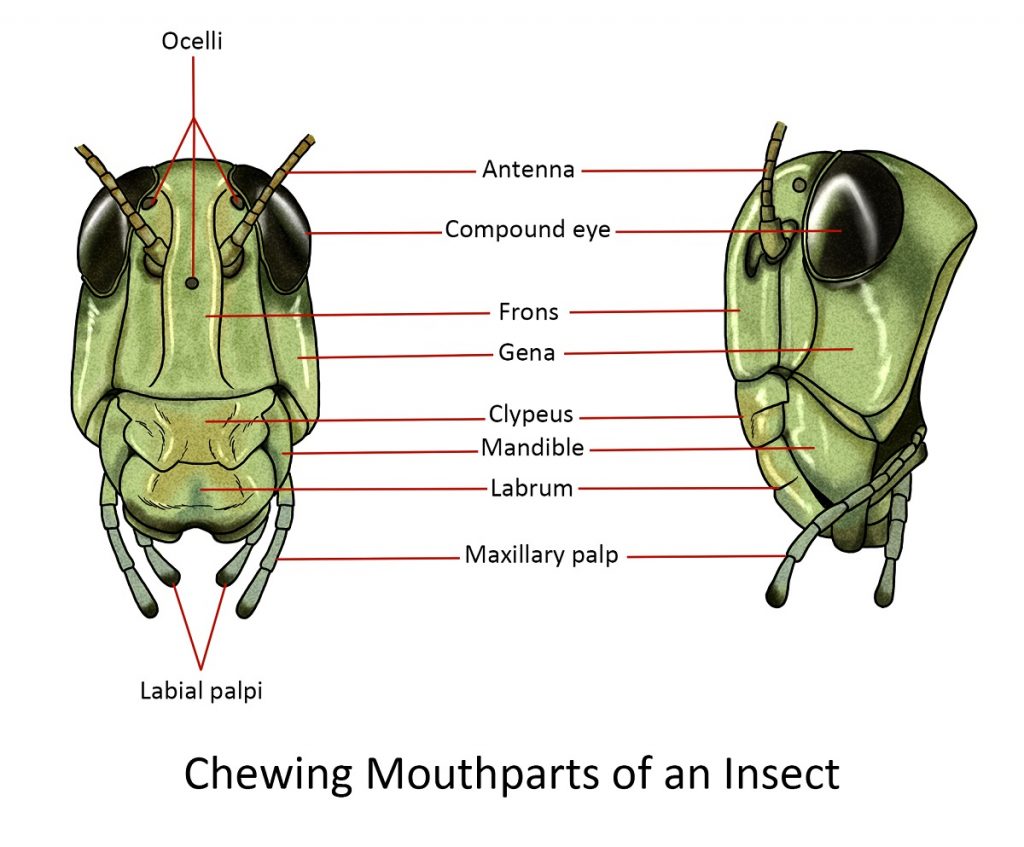

The principal organs used by insects for cutting and eating, aside from the legs are the mouthparts. There are many different types of mouthparts but the variety merely represents modifications of the basic arrangement.

Being able to identify and differentiate mouthparts can aid in insect identification. While there are many different types of mouthparts, the three are most commonly encountered:

Mandibulate or chewing

Insects that chew their food (e.g. cockroaches, adult beetles, grasshoppers) have the basic arrangement. Mandibular mouthparts usually have several parts:

The labrum or the upper lip is a flat structure hanging down from the clypeal area of the head. Behind the labrum is a pair of powerful jaws or mandibles that close in from the sides, like pincers.

Lying behind the bases of the mandibles is a relatively small opening, the mouth proper.

Posterior to the mouth mesally or in the middle is the tongue-like hypopharynx, behind which the salivary duct opens.

On either side of the hypopharynx is the less powerful pair of jaws, the maxillae. They are used for holding the food and feeding it between the mandibles to be crushed and sheared. The maxillae have an inner pincer-like lacinia and an outer hood-like galea, which acts as lateral lips to the mouth cavity. The maxilla also comes with a pair of segmented palps called maxillary palps that serve as sensory organs for smelling and tasting food.

The labium forms the lower lip of the mouth cavity; it also has a pair of segmented labial palpi bearing many sense organs often used for smelling and tasting food.

Piercing-sucking

During evolution, the basic chewing mouthparts were modified to enable the insect to 0piece tissues and suck juices. Insects that have piercing-sucking mouthparts include:

Members of the Order Hemiptera

- Plant suckers such as aphids, cicadas, and scale insects pierce the phloem of the plant through leaves, buds, stems, or roots and then suck the plant sap.

- Predators such as assassin bugs and water striders pierce through the cuticle of their prey and suck out their juices.

Parasites such as bedbugs (Hemiptera), lice (Phthiraptera), fleas (Siphonaptera) and mosquitoes (Diptera) pierce the skin of large animals such as birds and mammals and such out blood.

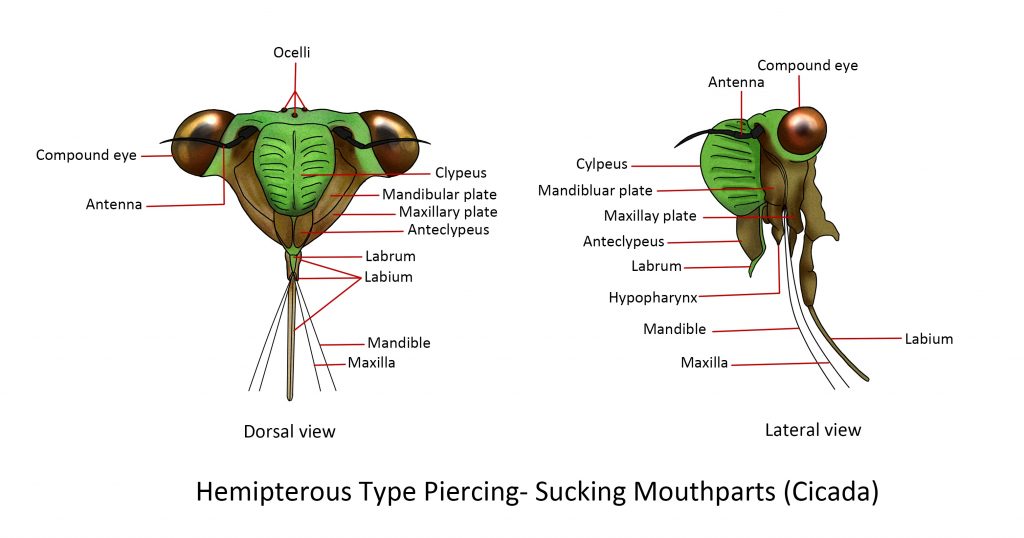

Hemipterous Type Piercing-sucking (Plant suckers)

The defining feature of the hemipterans is their modified mandibles and maxillae that form four “stylets”. Mandibular stylets are the definitive piercing organs that have barbed tips that help anchor themselves to their hosts. Maxillary stylets are fine-pointed, enlarged at their base and jointed to the maxillary plate by a lever. The stylets are sheathed within a segmented labium which serves as a protective covering. At the base of the labium is a triangular structure called a labrum. The main tube, called a food channel, is formed inside the median hypopharyngeal lobe and is used for sucking up juices to the digestive system. They also inject saliva into other organisms that may cause irritation and transmit diseases to plants, animals, and humans.

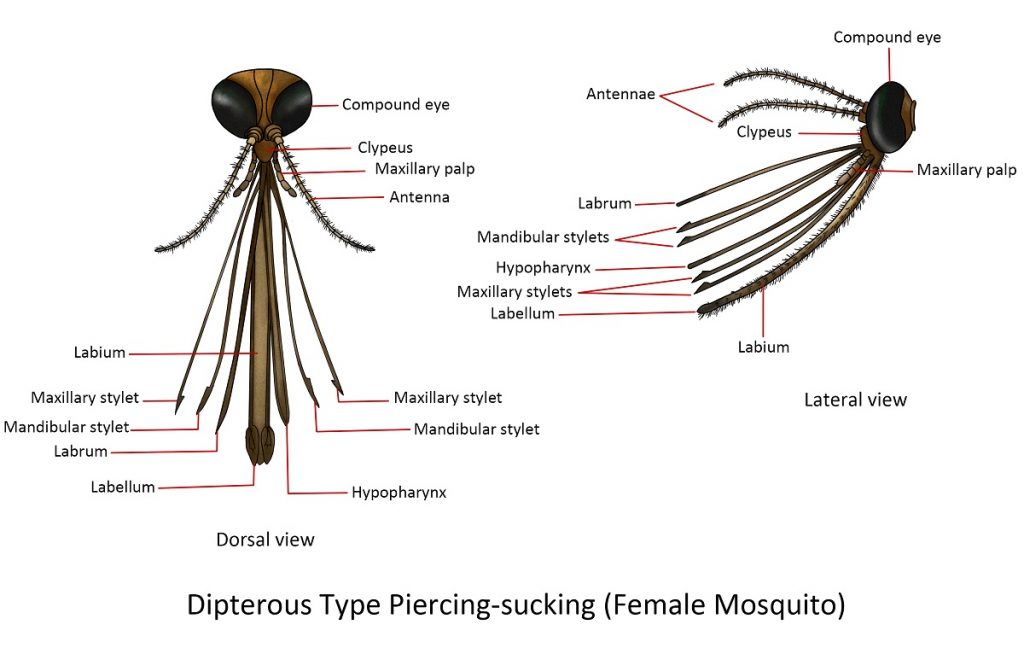

Dipterous Type Piercing sucking(Female Mosquito)

The bulging sclerite below the antennae and above the long proboscis is the clypeus. The body of the proboscis forms the labium which has a longitudinal furrow called the labial groove and a pair of small lobes at the apex, known as the labella. Six stylets can be drawn out of the labial groove namely: two heavier median stylets, the labrum-epipharynx and the hypopharynx; two pairs of slender stylets, the mandibular and maxillary stylets. The elongated and segmented maxillary palpi surround the proboscis.

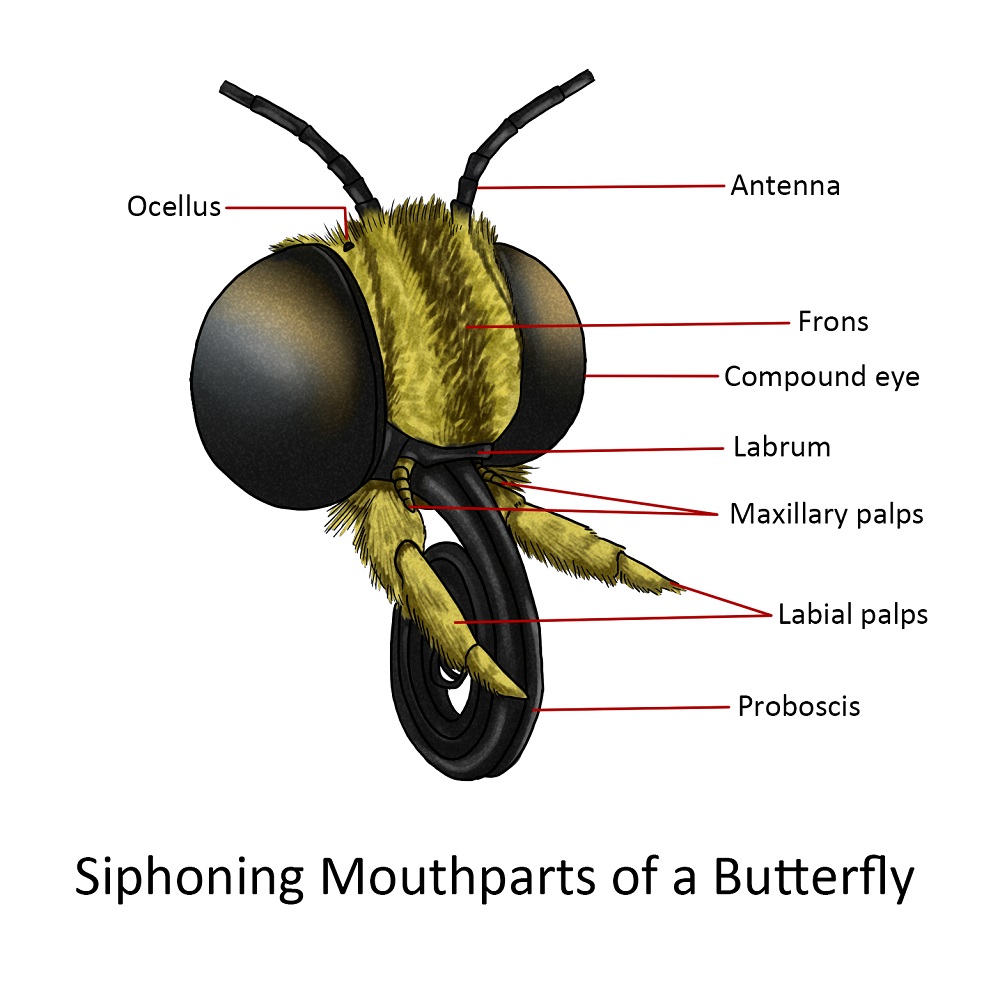

Siphoning

The mouthparts of Lepidopterans (moths and butterflies) have a totally different structure but a simple device for extracting nectar from deep flower corollas or imbibing exposed liquids. In many species, however, the mouthparts are either reduced, rudimentary or entirely absent and therefore take no food.

The labrum is usually a narrow band at the lower edge of the large frontoclypeal region, an area between the large compound eyes and below the bases of the antennae. On the lateral extremities of the labrum are pilifers, a pair of hairy lobes. The mandibles are entirely absent in the adult of most lepidopterous species but in some macrolepidopterous moths, they are reduced to rudimentary immovable lobes

The essential external part of the mouthparts of Lepidoptera is the proboscis or “tongue”. It is composed of two galeae which are held together by interlocking grooves; the joined galeae form a long sucking tube. The basal region of the mouthparts can be best seen from the ventral aspect of the head. The median region of the underside of the head consists of a membranous field in which the bases of the maxillae and labium are found. Each labial palpus is three-segmented with a small distal segment. The base of the labium is very vague and consists of a lightly sclerotized plate to which the bases of the palpi are attached. The maxillae are the most completely formed mouthparts; each maxilla consists of a cardo near the basal attachment of the labial palpus and can be best seen if one of the labial palpi is removed. The crescentic stipes are partly concealed by a mesal, sclerotized projection of the head.

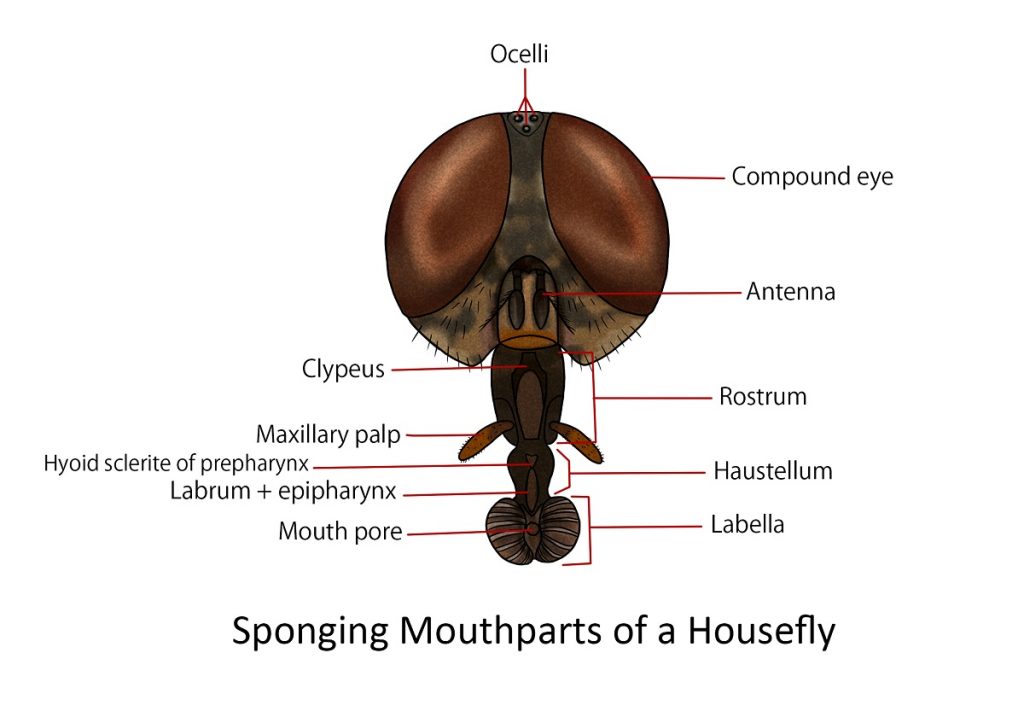

Sponging

An example of this type is the housefly. The proboscis of the housefly consists of three parts: the rostrum, the haustellum, and the labella.

The rostrum is a broad inverted cone with membranous walls. In the upper part of its anterior surface is an inverted V-plate, the clypeus. On the lower part of the anterior face of the rostrum are the pair of long maxillary palpus supported at their bases by two small lateral sclerites.

The cylindrical haustellum projects downward and slightly forward from the end of the rostrum. The anterior surface of the haustellum is covered by the long, tapering, strongly sclerotized, flap-like labrum. If the labrum is lifted, a deep, lengthwise cavity is exposed in the anterior part of the haustellum and in here lies the blade-like hypopharynx. Between the labrum and hypopharynx is the food canal which leads to the functional mouth.

The labellar lobes are broad pads at the terminal portion of the proboscis, they form an oval disc when spread out flat, crossed by pseudotracheal channels and enclosing a central opening. The oral aperture. Anterior to the aperture and between the labellar lobes is the prestomium whose inner walls in some flies are armed posteriorly by rows of small prestomal teeth.

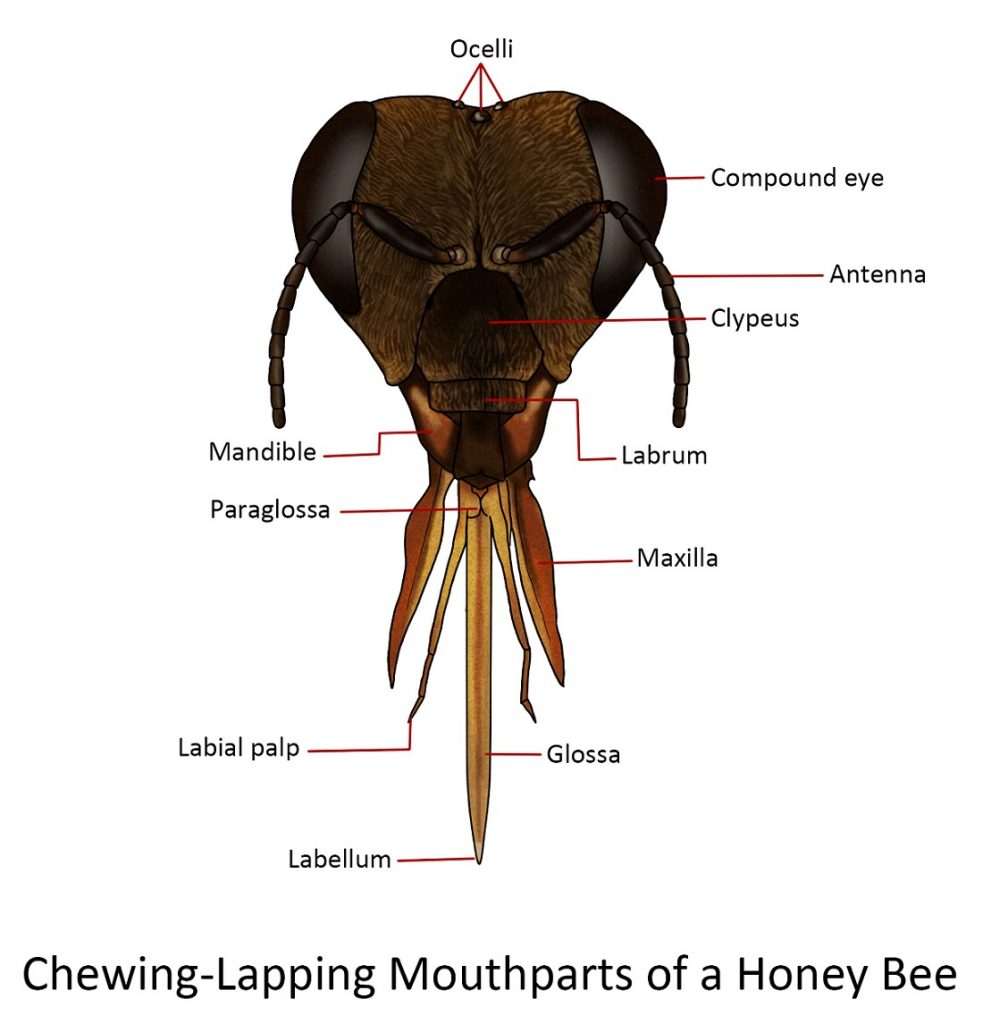

Chewing-lapping

The general structure of the combination mouthparts follows the usual pattern of the mandibulate type, except that the mandibles are small and blunt and are used to mould wax for the honeycomb. A new structure has also appeared, the “proboscis”, with which the nectar is collected during foraging and honey is manipulated in the hive.

The “proboscis” is a composite structure composed of the fused labium and maxillae. The lateral divisions consist of the maxillar and the longer median division of the labium.

Each maxilla consists of an elongate, proximal cardo followed by the more robust stipes. At the lateral, distal end of the stipes is the small maxillary palpus. The stipes bear distally the large blade-like galea. The only part missing on the maxilla of the honeybee is the lacina, although some professionals believe it has fused with the blade-like galea to form what they call mala.

The labium of the honeybee is quite complete., The small triangular plate at the base of the labium is the mentum. The inverted V-shaped sclerite that joins the mentum of the labium to the cardines of the maxillae has been called lorum and is believed by some authors to be part of the base of the hypopharynx, which may have been incorporated into the complex known as “tongue” or “glossa”. The large prementum is distal to the mentum. The lateral appendages attached to the distal end of the prementumare the four-segmented labial palpi. Between the bases of the labial palpi and the fussed glossae are a pair of small processes, the paraglossae, which are very lightly pigmented.

The labrum is a small, flap-like structure below the clypeus which is the central part of the head below the antennae.

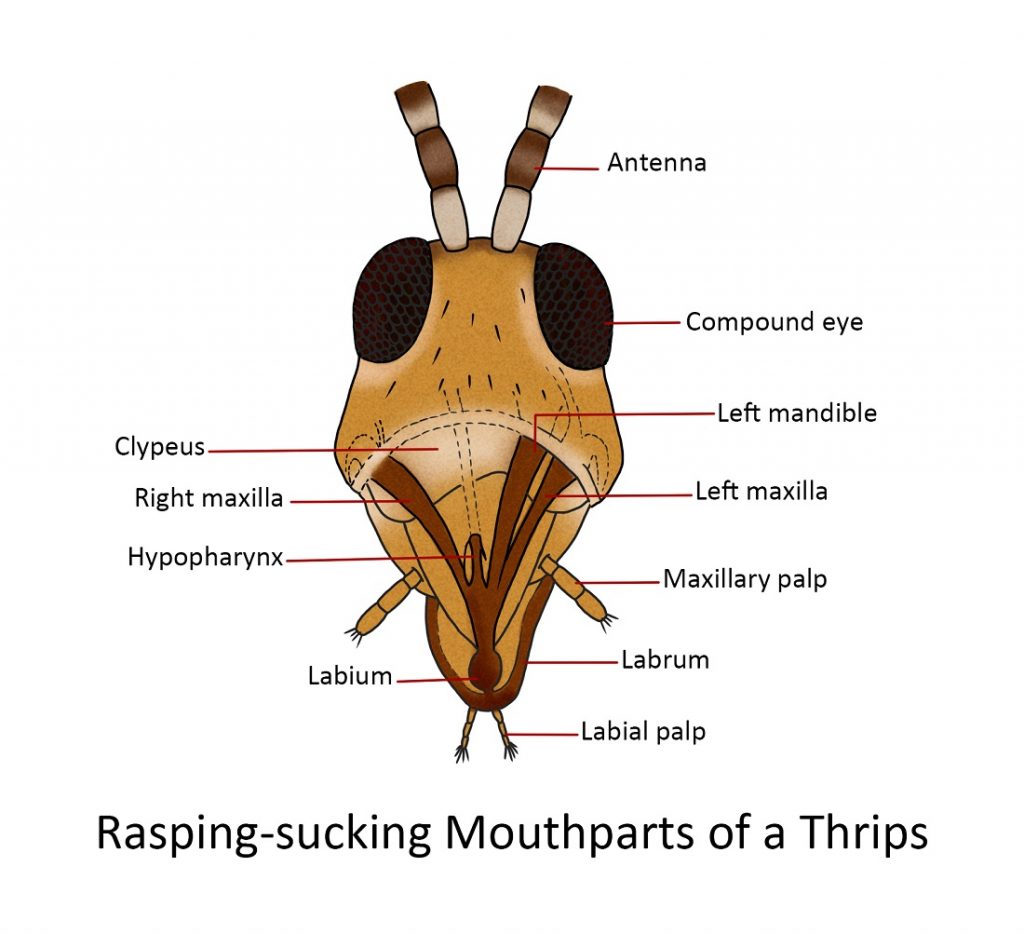

Rasping-sucking

The mouthparts of thrips are more generalized than those of Hemiptera but are more unusual in some respects.

The distorted head of the thrips bears a short, thick, conical beak that projects downward from the posterior part of the undersurface. The beak is formed by the labrum on the anterior surface, the maxillae laterally, and the labium posteriorly. Within the beak are the left mandible (the right rudimentary mandible), two piercing stylets associated with the maxillary bases, the hypopharynx and the labium bears a pair of short labial palpi. The oval surface of the labrum is folded at the apex into a deeply channelled epipharynx.

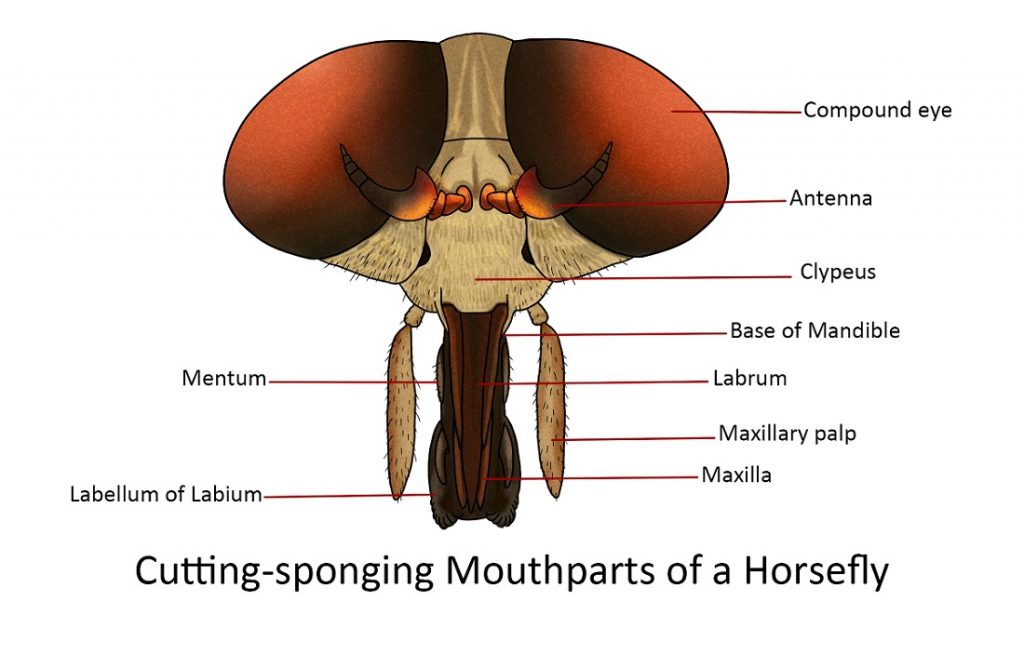

Cutting-sponging

The mouthparts of several adult flies (e.g. horse fly) form a compact group of nine pieces. Three of these are unpaired: the labrum, hypopharynx and labium. The other six are the paired mandibles, maxillae, and maxillary palpi.

The dagger-shaped labrum is the most anterior of the unpaired median organs. Its lateral edges are overlapped by the large two-segmented maxillary palpi. Beneath the labrum are two pairs of long, slender, tapering blades, the mandibles, anteriorly and the maxillae, posteriorly. The mandibles are flattened, sharp-pointed blends with their tips reaching the apex of the labrum. Their piercing thrust is made by a forceful action of the head and body of the fly. Each maxilla consists of a basal part composed of the cardo, and stipes, a large, thick, two-segmented palpus and along, slender, tapering blade-like glaea.

The long, narrow, tapering stylet-like hypopharynx lies in the deep groove of the anterior face of the labium, the latter being a large, thick, elongate appendage ending in two broad lobes or labella.

Thorax

The thorax is the region of the insect’s body that lies between the head and the abdomen. It consists of three segments: the pro-, meso-, and metathorax. All three segments bear a pair of legs, and in addition, a pair of wings on the meso- and metathorax, which are collectively called the pterothorax.

The prothorax is sharply differentiated from the pterothorax and never develops wings. The tergum is known as the pronotum and it forms a shield-like plate that extends towards the posterior, giving some protection to the prothoracic segments. The mesothorax bears the middle legs and the forewings of the insect (if present), while the metathorax bears the hindlegs and hindwings (if present).

Legs

Typically, the usual segments of the legs are:

The coxa – the first segment of the leg. It is attached to the coxal cavity of the body by an articular membrane, the coxal corium. Distally it is joined to the second segment by an anterior and posterior articulation.

The trochanter – is a small segment freely movable by a horizontal hinge to the coxa but fixed to the base of the third segment.

The femur – is usually the longest and stoutest part of the leg, although it varies in size in different groups of insects or stages of development.

The tibia – is a slender segment, usually shorter than the femur. The proximal end is bent toward the femur, allowing it to be flexed close to the undersurface of the femur. In some insects, on its posterior surface, there usually are spines and on its apex movable spine-like processes called spurs.

The tarsus – in adult insects is usually subdivided into subsegments or tarsomeres. The tarsomeres may vary from 2 to 5 and the basal tarsomere is sometimes enlarged and called basitarsus. In certain Orthoptera (Grasshoppers, crickets, katydids), small pads called pulvilli are present under the surfaces of the tarsal subsegments or they may appear as lateral lobes of the pretarsus arising beneath the bases of the claws.

The pretarsus – is the terminal segment of the leg bearing, usually a pair of movable lateral claws and a median lobe, the arolium. In Diptera (flies and mosquitoes), in addition to the two large pulvilli, one beneath each claw is a median process called empodium which is spine-like or lobe-like just like the pulvilli.

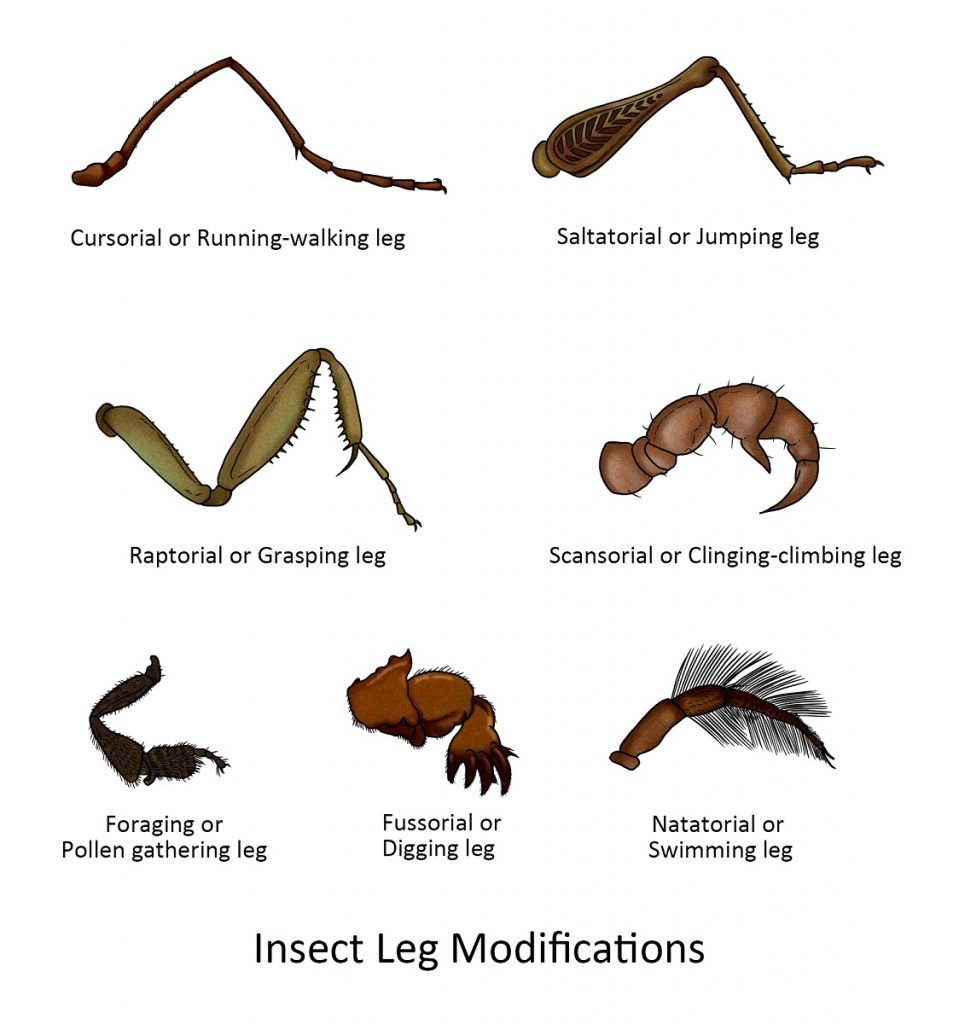

The legs of insects vary in shape and size according to their habits and habitats. Some of the more striking modifications are illustrated below.

Wings

Insects are the only invertebrates with wings. Most adult insects have two pairs of wings; some have only one pair while they evolved the second pair into a balancing organ during flight. Wingless insects such as silverfish and springtails are primitively wingless and have never developed wings, while bedbugs, fleas, lice, and some cockroaches are believed to have winged ancestors but had no reason to keep their wings because of their lifestyle. Reproductive termites or alates remove their wings after a mating flight.

The insect wing is a flattened, double-layered extension of the body wall. Its structure has three features: the articulation to the body, the veins, and the differentiation of the wing surface into regions.

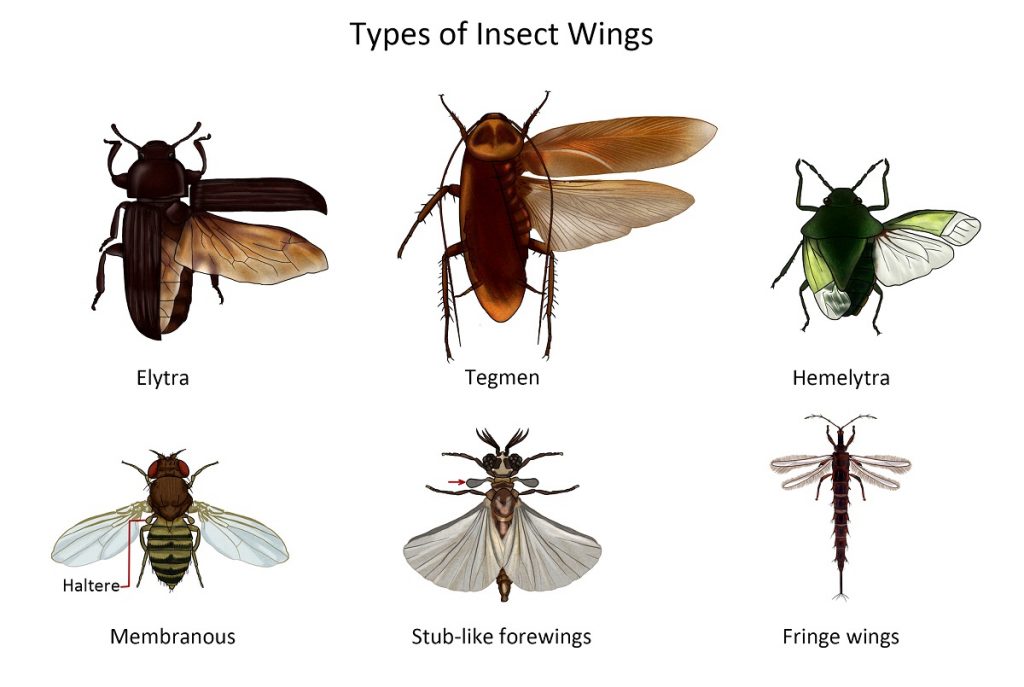

Specialization, texture and vestiture of wings

In many insects, the forewings become more sclerotized for the protection of the hindwings when not in use. In others, both wings are delicate membranous structures clothed with thick fine hairs sometimes variously pigmented. In a few, the wings may be reduced or wanting.

The forewing of grasshoppers and cockroaches is thickened and parchment-like in texture but the veins are still distinct. It covers the delicate membranous hindwing in a roof-like manner, hence the name tegmen.

In beetles and earwigs, the entire forewing is thick and has ridges instead of veins are present. It is called an elytron (plural elytra) because of its horny or highly sclerotized character.

Other insects such as the true flies (Diptera), bees, wasps and ants (Hymenoptera), dragonflies and damselflies (Odonata) have wing cells that are thin and membranous. Their transparency or translucency, however, may be obscured by various colour pigments, hairs or scales.

The forewing of true bugs (Hemiptera) is modified such that the basal ⅔ to ¾ of the wing is parchment-like while the remaining distal part is membranous, hence the name hemelytron (half-elytron, plural hemelytra).

Members of the order Strepsiptera have stub-like forewings while those of thrips are a pair of short, narrow, fringed wings, though some are wingless. Ptilidae (the smallest known beetles) have narrow wings, fringed with long setae but without veins.

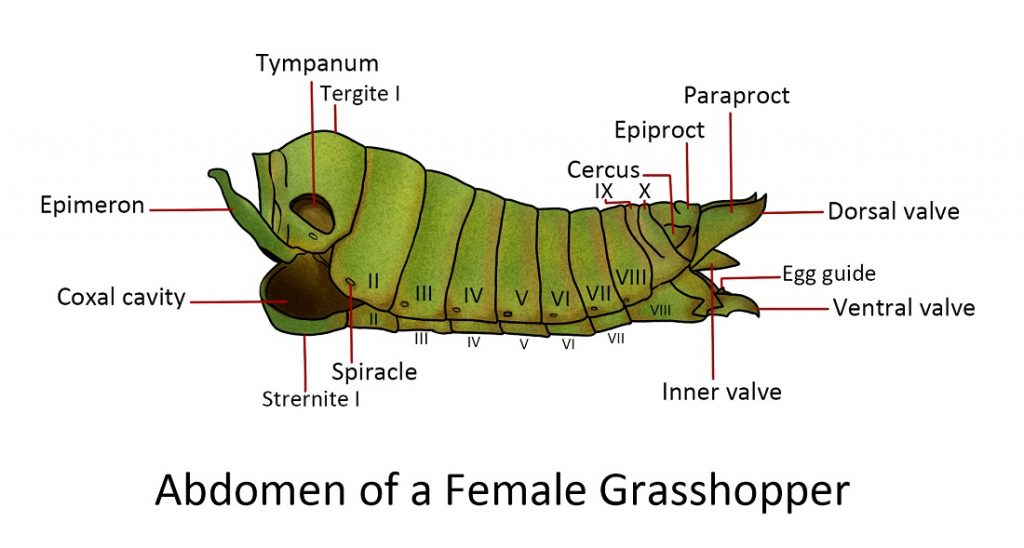

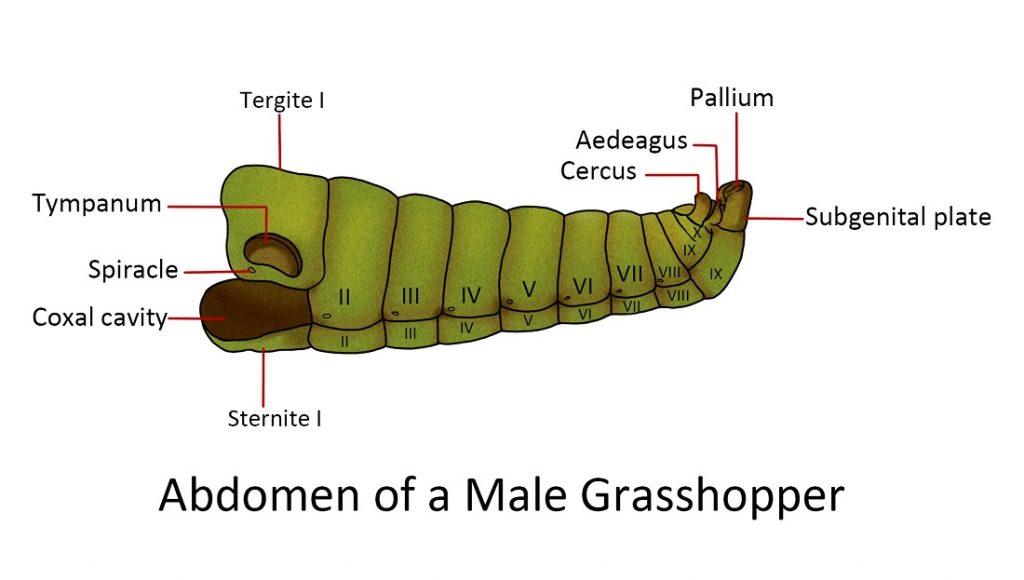

Abdomen

simple structure and lack of appendages in the anterior segments. The usual number of abdominal segments in adult insects is 10 or 11. Each segment consists of a tergum and sternum joined by a membranous pleuron. The front margins of each segment overlap the anterior part of the segment behind, creating a “telescope”. This allows the abdomen to expand and contract in response to muscle movement. At the very end of the abdomen, the anus or the opening of the digestive system is located between the sclerites – the epiproct and a pair of lateral paraprocts.

Appendages of the abdomen:

The cerci are leaf-shaped sensory organs that detect touch and air movement. They

may be located near the anterior margin of the paraproct. They are regarded as a primitive feature because they are absent in Hemipterans and insects with a complete metamorphosis.

Reproductive appendagess. In male insects, the penis is associated with a pair of external reproductive organs called claspers. The ninth abdominal segment is joined with the tergum of the tenth segment and its sternum is enlarged forming the hood of the claspers which are used to grip the female during copulation. Females, on the other hand, have an egg-laying organ called an ovipositor. Ovipositors vary in appearance depending on the insects; they can be sword-like, needle-like, short with horns, modified into a stinger (e.g. worker honeybee) etc.

Prolegs. The larvae of butterflies, moths, and other insects have fleshy unjointed projections on the abdomen called prolegs, sometimes called false legs or pseudopods. They supplement the three pairs of thoracic legs of the larvae for locomotion. Caterpillars may have five pairs of prolegs during their larval stage.

Internal Morphology

The internal morphology of insects is simple which to some extent is related to their small size and to a more considerable degree to the attainment of an efficient skeleton as a supporting and protecting device. The amount of special internal connective tissue is insignificant since the integument, through the tracheal system, provides most of the internal support for the organs. This lack of bulk played an important role in the development of insects to fly.

Internal components

Food ingested by insects and other animals undergo a metabolic process that releases energy that enables the animal to grow, move and function. Insects utilize food and oxygen significantly differs from those used by higher animals, such as humans.

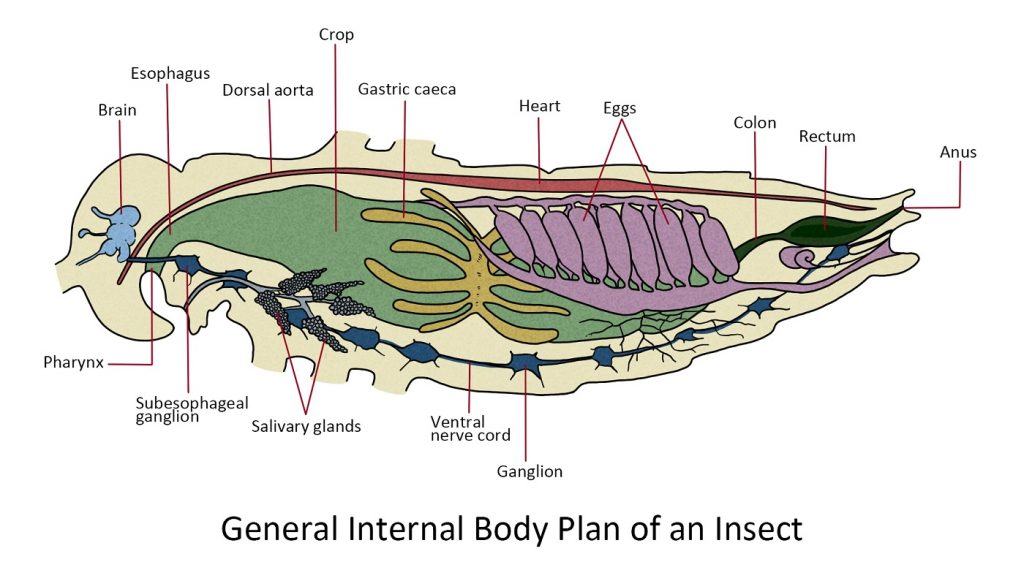

Before diving into specific systems of the insect body, let’s first look at the general plan of an insect body that encapsulates a variety of tissues and organs.

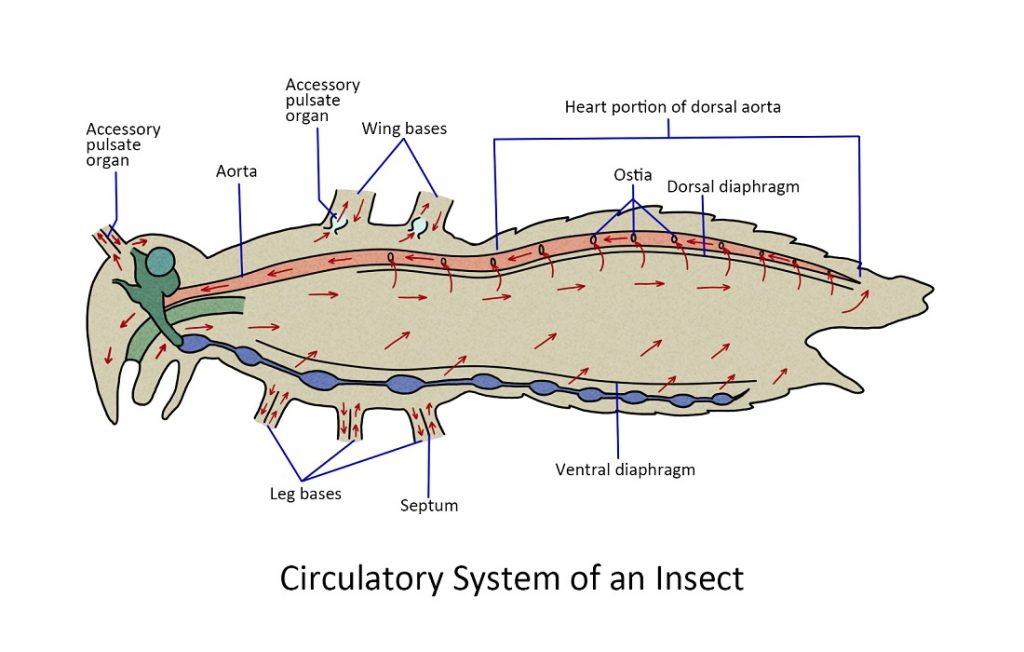

Insects do not have blood like vertebrates and mammals do. Their “blood” is called hemolymph, and while it serves a similar role to that of blood, it is different in certain significant ways. Unlike mammals and reptiles, insects have an open circulatory system that lacks veins and arteries. The hemolymph flows freely inside the hemocoel or insect’s bodily cavity and bathes all the tissues and organs. It is circulated by a dorsally located ‘tubular pump’.

The digestive system or alimentary canal is a just basically a tube that runs through the body with an opening at each end that absorbs nutrients from the food ingested. The nutrients filtered through the gut wall are picked up by the hemolymph. The digestive tract also has extraction sections that absorb waste products from the hemolymph. These waste products are returned to the alimentary canal along with non-absorbed food and will be ejected through the anus.

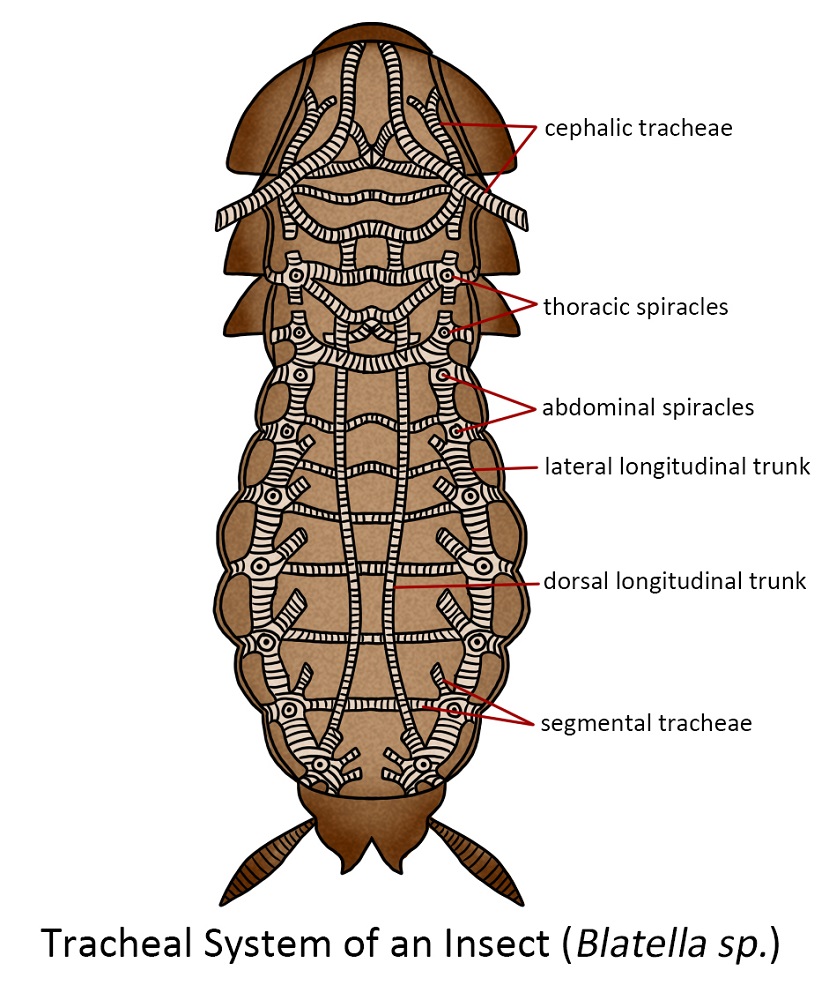

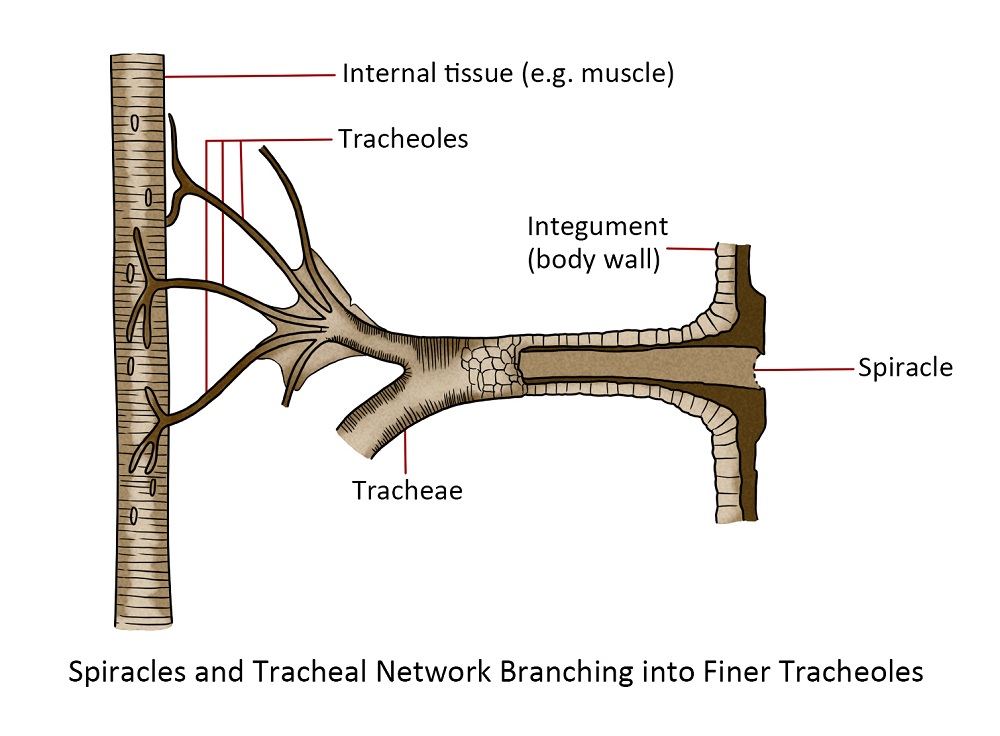

Oxygen is delivered to the tissues by the tracheal system, a network of pipes that start from the spiracles or holes on the exoskeleton that allow air to enter the trachea. These pipes branch into smaller and smaller pipes to deliver oxygen to cell sites that require it.

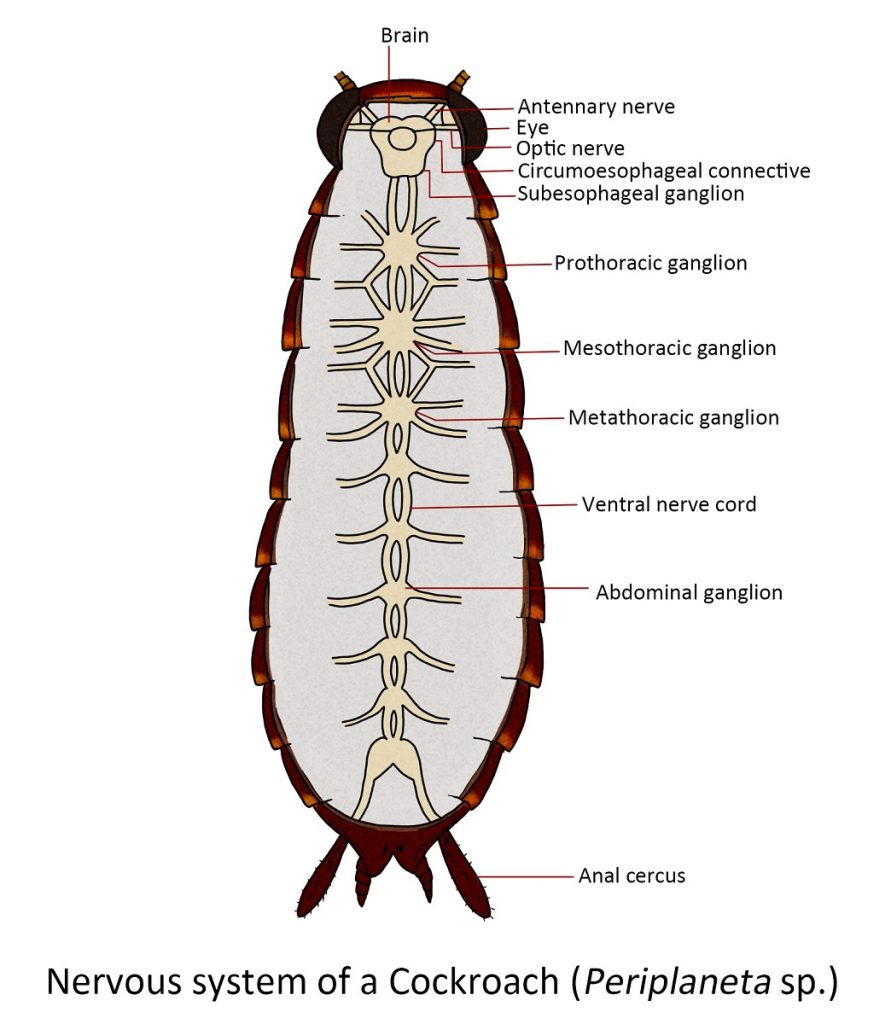

The central part of the nervous system is a double nerve cord located ventrally. It branches into finer nerve cells that diverge throughout the body to collect information and signal tissues and parts to perform actions. Additional regulation of physiological functions and behaviour is accomplished through the secretion of “chemical messengers” by significant glands. These messengers consist of hormones, which regulate the individual insect’s body, and pheromones, which convey information among members of the same species.

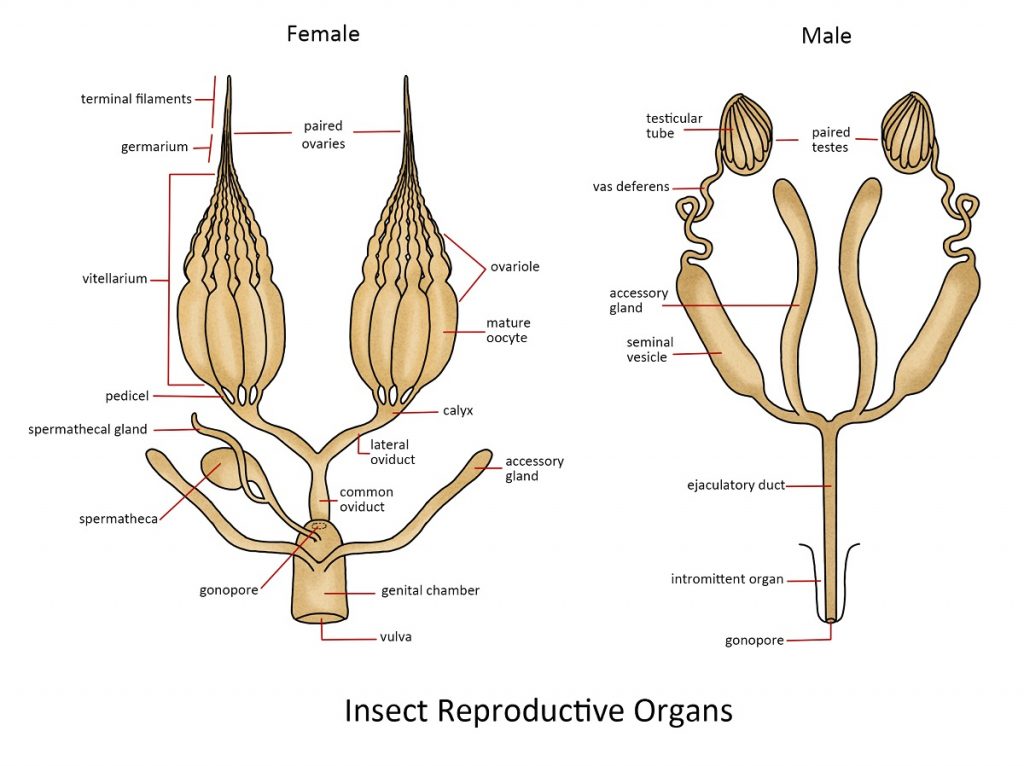

The reproductive system of insects is generally found inside the body cavity at the posterior end. For males, they serve to develop sperm, and eggs in females.

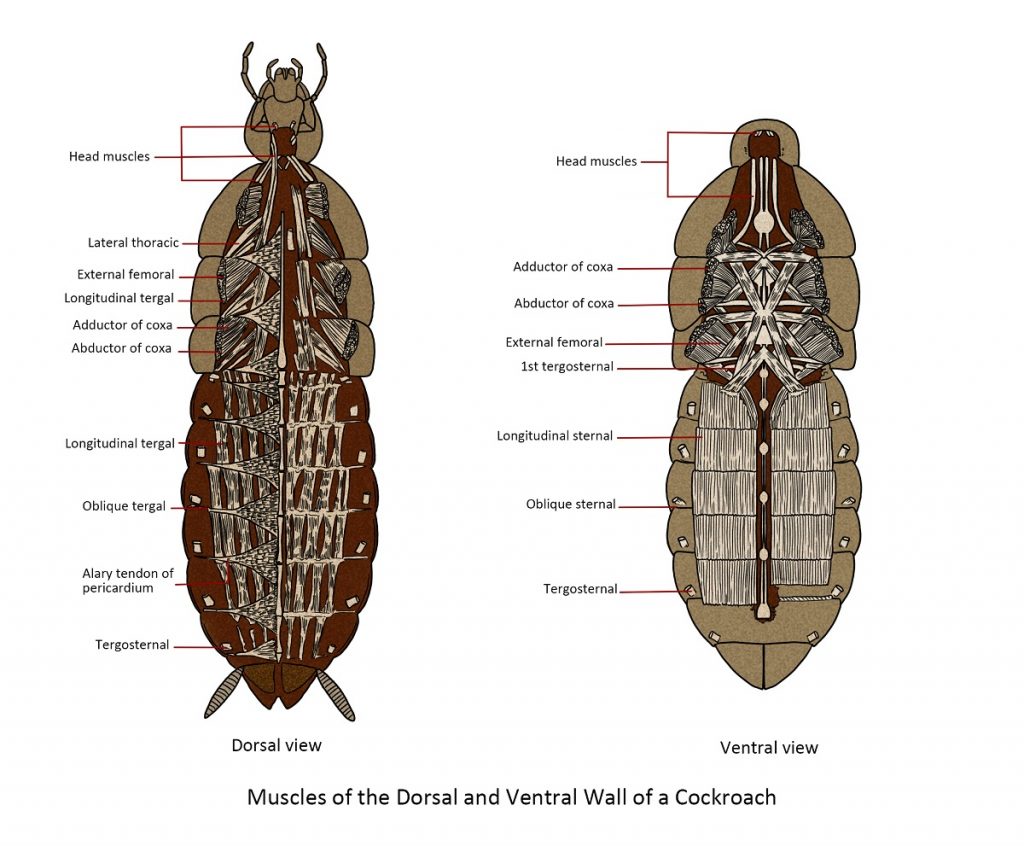

The muscular system of insects, not only powers flight and running, but also the tubular pump that circulates the blood.

Lastly, since food is not always readily available to insects, the majority of them have a system for transforming food into storable fat which can be used when needed.

The Haemocoel is a cavity that provides the internal environment of the cells and tissues that make up the body of the insect.

Circulatory system

Unlike vertebrates and mammals, insects do not have blood. Instead, they have what is called the haemolymph.

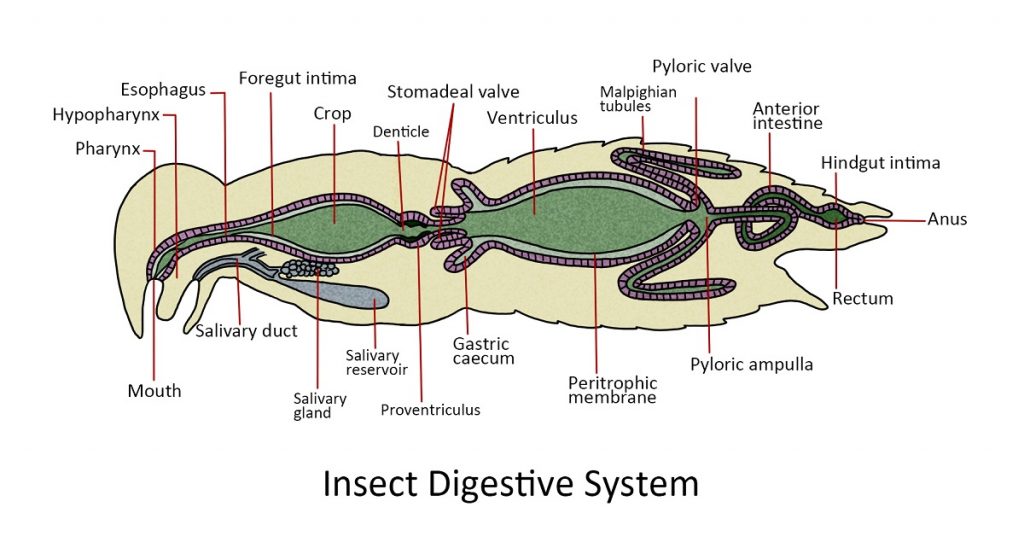

Digestive System

The digestive tract or the alimentary canal is divided into the regions: the foregut or stomodeum, the midgut or mesenteron, and the hindgut or proctodeum.

The foregut or stomodeum. Food enters the mouth cavity (pharynx), a muscular valve that marks the front of the foregut located centrally at the base of the mouthparts. The food is passed down the esophagus to the crop, an organ where food may be stored prior to digestion. Food from the crop passes through the gizzard or muscular proventriculus which has tooth-like denticles that grind and pulverize food. The proventriculus also acts as a valve to the midgut.

The midgut or mesenteron. This region is the primary site for digestion. Near the anterior end are finger-like projections called gastric caecae, that diverge from the walls of the midgut. It provides extra surface area for the secretion of enzymes. The rest of the midgut is called ventriculus. It is where the primary site for the enzymatic digestion of food and absorption of nutrients.

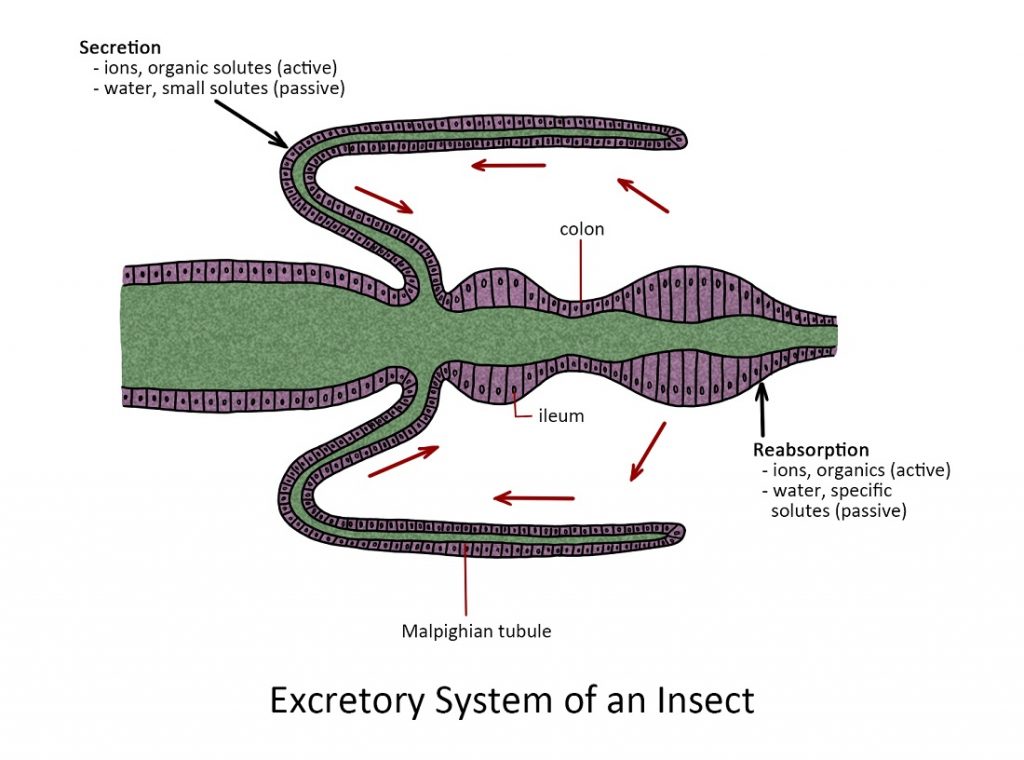

The hindgut or proctodeum. The pyloric valve is the point of origin of Malpighian tubules. They are long, spaghetti-like structures that extend throughout most of the abdominal cavity where they function as excretory organs that remove nitrogenous waste from the hemolymph. The nitrogenous waste (NH4+) is converted to urea and then uric acid by a series of chemical processes within the Malpighian tubules. The uric acid accumulates inside each tubule and is eventually ejected into the hindgut through the anus as a part of the fecal pellet.

The rest of the hindgut plays a major role in regulating the absorption of water and salts from waste products in the alimentary canal. In some insects, the hindgut is visibly subdivided into an ileum, a colon, and rectum. These organs remove more than 90% of the water from a fecal pellet before it passes out of the body through the anus.

The function and structure of the digestive and excretory systems are linked to diet and may vary from insect to insect. Regarding the nutritional needs necessary for survival, growth, and development, insects, similar to mammals, must consume a typical range of food substances. They often require substantial amounts of energy-providing compounds, such as sugars and fats. Amino acids from protein, vitamins and minerals are the most important components of the diet. Although insects have different dietary requirements, all insects require water as all cell functions rely on solvent properties.

Termites and wood cockroaches do not produce enzymes to break down cellulose, instead, they have a symbiotic relationship with microorganisms called protozoa that digest cellulose into products that the insect can absorb and utilize.

The digestive system of insects plays a vital role in the effectiveness of insecticides as they need to enter the mouth and be ingested. Insecticides that act through the digestive system are referred to as “oral” or “stomach” poisons. This type of control takes advantage of the grooming habits of insects, as seen in instances like the ingestion of dust by termites, cockroaches, and other insects.

Excretory System

Nervous and Glandular Systems

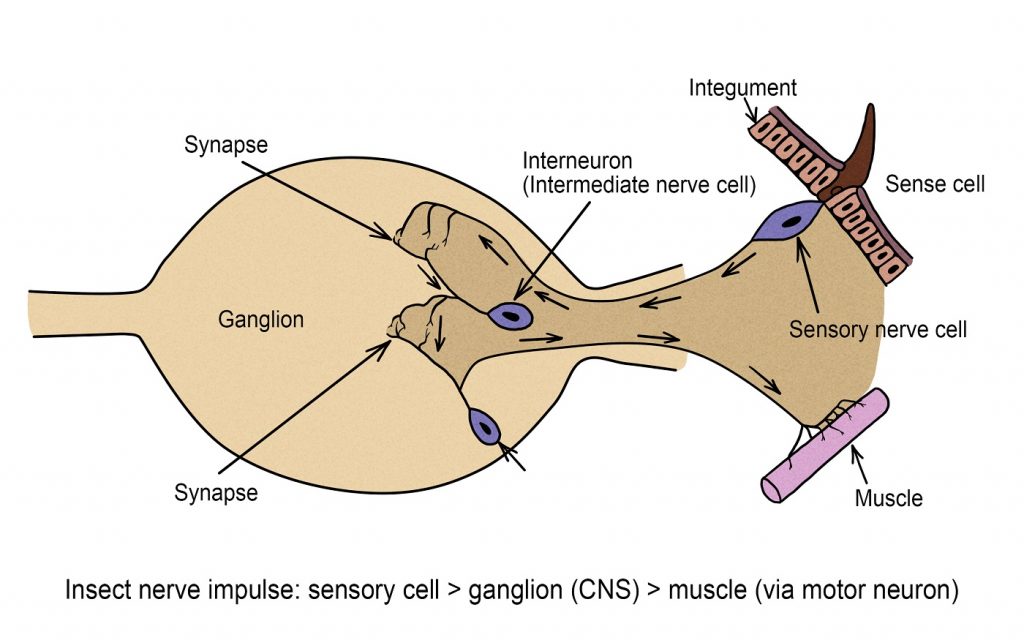

An insect’s nervous system comprises a complex network of specialized cells known as neurons, functioning as a communication network within the body. These neurons produce electrical impulses, referred to as action potentials, which propagate as depolarization waves along the cell’s membrane. Each neuron consists of a central nerve cell body containing the nucleus and thread-like extensions, including dendrites, axons, or collaterals, which transmit the action potential.

Insects have a range of sensory mechanisms to perceive information about their surroundings. These can be broadly summarized as follows :

Touch – tiny hairs, spines, bumps or other structures distributed widely over the body but sometimes concentrated on the antennae, cerci, or other parts.

Smell – hairs or pits associated with the antennae and mouthparts.

Taste – hairs commonly found on mouthparts but sometimes located on the antennae and tarsi.

Sight – compound or simple eyes (ocelli) on the head.

Hearing – various structures found on the abdomen, legs, thorax or other parts.

Many insecticides currently depend on interfering with the nervous system as a mode of action. Synthetic pyrethroids impact nerve cell axons, whereas organophosphates and carbamates disrupt the function of cholinesterase enzymes at synaptic junctions.

Nervous System

Granular System

The glandular systems include:

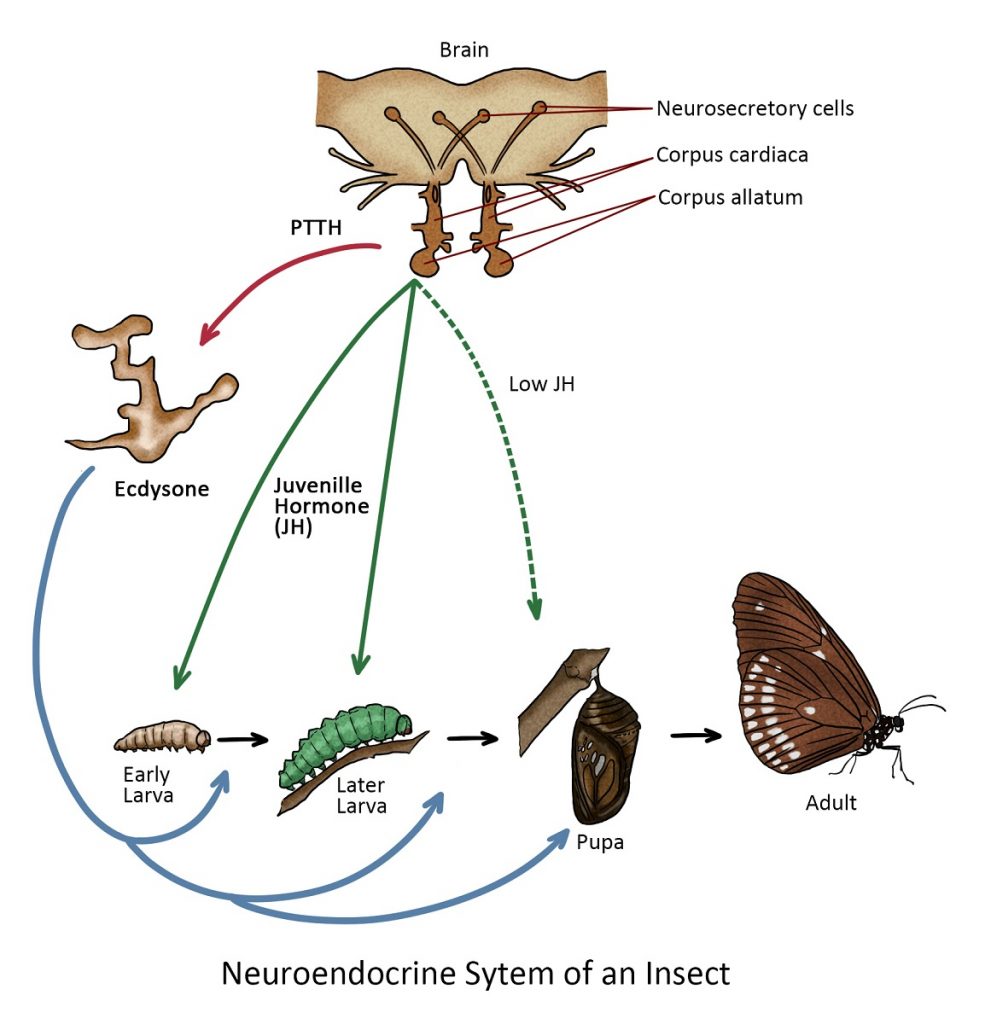

- Endocrine glands – responsible for regulating various physiological processes, growth and development. These glands, including the prothoracic gland, corpora allata, and the corpora cadiaca, secrete hormones that play vital roles in insect biology.

- Exocrine glands – responsible for the secretion of various substances outside the body, typically into the external environment. These glands play an important role in communication, defence, feeding, and other ecological functions.

Endocrine glands

While the endocrine system is largely responsible for controlling activities that require instantaneous reactions such as fleeing from a predator, and long-term changes such as growth and development are controlled by the glandular secretions known as hormones.

The prothoracic gland secreted ecdysteroids, such as ecdysone, which regulate molting and metamorphosis. Ecdysteroids trigger the shedding of the old exoskeleton (ecdysis) and the development of a new one during insect growth and metamorphosis.

The corpora allata gland produces juvenile hormones, which are involved in controlling various aspects of development, including preventing insects from undergoing metamorphosis too early. Juvenile hormones also influence reproduction and caste determination in social insects like ants and bees.

The corpora cardiaca gland secretes hormones that are involved in regulating reproduction and sexual maturation. In some insects, these hormones influence processes like mating behaviour and egg reproduction.

Exocrine glands

These glands are responsible for secreting substances outside the insect’s body. Examples are salivary and silk gland secretions for defence and glands that secrete pheromones.

Pheromones are chemical compounds that play a crucial role in communication and behaviour within insect populations. These chemical signals are produced and released by insects into their environment, and they can affect the behaviour or physiology of other members of the same species. Pheromones are volatile chemicals received as odours, and some are transferred between individuals through direct physical contact. These chemical signals have various roles such as attracting mates for sexual reproduction, regulating social roles within colonies (as seen in social insects like ants, bees, and termites), promoting group behaviour like the clustering of cockroaches, marking trails to aid ants in location food sources, and signalling alarms (often done by social insects to warn of potential threats).

Synthetic pheromones, usually sex attractant or aggregation types, are used in traps for monitoring various stored product pests.

Endocrine System

Reproductive System

The reproductive systems of insects have developed to produce enormous numbers of offspring. While there are some insects that produce less than 100 offspring in their whole adult lifetime, others can produce thousands per day. Most insects reproduce by finding a mate of the opposite sex via sound, pheromones, visual displays, and other courting rituals, and then mating. This type of reproduction relies on the fertilization of females by males. Meanwhile, some insects reproduce asexually via a process called parthenogenesis — a process by which the female eggs get fertilized without the fusion of male sperm.

Male Reproductive System

The male insect’s reproductive system is specialized for producing and transporting sperm. Situated in the abdominal region, two testes produce sperm cells, which travel through the vas deferens tubes into sperm sacs where they are stored. Secretions from accessory glands are combined with sperm cells before they pass through the ejaculatory duct to be released through the penis. Typically, the male genitalia consists of the penis and sometimes a pair of claspers, which help in the process of copulation.

Female Reproductive System

The female insect’s reproductive system is tailored for the production of eggs, sperm storage, egg fertilization, and egg-laying. Each female insect possesses a pair of ovaries, which can consist of one to several hundred ovarioles. Eggs generated in the ovarioles travel down the lateral oviducts to reach the median oviduct (vagina). Fertilization of the eggs can occur as they pass by the opening of the spermatheca, an organ responsible for storing sperm obtained during copulation with a male. Eggs passing through the accessory gland may undergo various treatments. In some insects, they are coated with a sticky substance for adhesion to leaves or other surfaces, while in the case of cockroaches, the eggs are enclosed in protective egg capsules or oothecae. The female’s external genitalia often feature a prominent structure for egg-laying known as the ovipositor. In most insects, each individual female of the species is responsible for producing new offspring. However, in social insects, the majority of the colony’s population is effectively sterile, and reproduction is carried out exclusively by the reproductive castes. This can mean that a colony of over 2 million termites, for example, relies solely on the efforts of a single reproductive pair.

Respiratory System

Every living creature requires oxygen to break down food molecules and harness the energy they contain. As a result of this process, carbon dioxide is produced as a waste product and needs to be eliminated. In more advanced animals, such as humans, the blood plays a crucial role in transporting oxygen from the lungs to every cell in the body and in disposing of the waste carbon dioxide generated at the cellular level.

The majority of insects accomplished the delivery of oxygen and the removal of carbon dioxide through a system of interconnected tubes or air channels. Typically, insects possess approximately ten sets of spiracles situated along the sides of their thorax and abdomen. These openings lead to tubes that have a spiral thickening of the cuticle and are known as the trachea. Although there are typically a few large longitudinal tracheal passages, the trachea divides and continues to divide, gradually reducing in size until there is a vast quantity of minuscule tubes connecting to the cells of various tissues and organs. These tiny tubes are called tracheoles, and their final interaction with the cells facilitates the diffusion of gases, especially oxygen, directly into the cells.

In slow-moving or less active insects, the mechanism functions primarily through the diffusion of gases along the intricate tracheal network, delivering oxygen to the cells and removing carbon dioxide. Typically, spiracles can be sealed, a strategy likely adopted to conserve water within the insect’s body. In more active insects, which have an increased need for oxygen, this demand is typically met by enlarging specific tracheae to create air sacs. This adaptation, coupled with purposeful ventilation, enables a rapid exchange of air, which is essential for energy-intensive activities.

The respiratory system of insects, known as the tracheal system, provides a significant pathway for the penetration of specific insecticides. Fumigation methods involve subjecting insects to a toxic environment that kills when inhaled. Some insecticides are recognized for their toxicity when inhaled. Additionally, certain contact insecticides can dissolve in the waxy outer layer of an insect’s cuticle and then migrate into the insect through the openings of their spiracles.

Muscular system

The insect muscular system is a complex network of numerous muscles in many species. It converts chemically stored energy into mechanical energy, which results in various movements. Muscles consist of bundles of strap-like fibres and function by contracting. While most animals use muscles for major activities like searching for food, mating, or escaping adverse conditions, different sets of muscles also have a crucial role in internal functions such as blood circulation and digestion.

The muscles responsible for moving your elbow are connected to the bones on both sides of the joint. When you intend to bring your hand towards your face, the relevant muscles attached to your upper arm contract, These muscles, being connected to your forearm, result in the elevation of your forearm and the visible bulging of your bicep muscle. Insects, on the other hand, possess an external exoskeleton, which provides them with a significantly expanded surface area for attaching their muscles.

Similar to the mechanics of your elbow, insect muscles are connected, with one end attached to the inner part of the femur’s cuticle and the other end extending through the joint to the inner part of the tibia. When these muscles contract, they alter the angle between the segments of the leg at the joint, enabling various forms of movement such as walking, running, crawling, burrowing, swimming and flying. Despite their small size, insects exhibit remarkable strength relative to their body weight; in some cases, they can lift many times their own weight. Nevertheless, it is in the realm of flight that insects truly shine. Few other animals have developed muscles capable of contracting and relaxing at such an extraordinary rate, allowing them to achieve wingbeat frequencies of 1000 beats per second. This remarkable power of flight has made insects the most agile and widely dispersed group of animals in the world.

Food storage system

Insects often face challenges in obtaining food promptly when required, which is why many of them possess adipose tissue, also known as the fat body. This fat body consists of a loosely structured collection of cells distributed throughout the body cavity. Adipose calls are frequently noticeable as irregularly shaped, whitish substances that are densely distributed around internal organs and within the body wall, primarily located in the abdomen.

Young insect stages frequently accumulate fat bodies, primarily storing lipids or fats, protein, and glycogen, which are later utilized. In many cases, larval forms store substantial food reserves to support the transformations during the pupal stage and serve as a course of nourishment for their adult stage. Insects that stop feeding in their adult stage depend entirely on the food reserves they accumulate during their juvenile stages to meet their energy needs.